“I don’t think one parent can raise a child. I don’t think two parents can raise a child. You really need a whole village.” — Toni Morrison

Here’s something I never would have noticed if I weren’t the parent of a child in a wheelchair: The places where parking for disabled people is always full and the places where it never is.

The hardest places I’ve found to use my son’s disabled parking permit?

Walmarts in low-income areas.

Funny? Right? Until you start to really think about why disability and the need for low-cost groceries go hand-in-hand.

How about disability and stress? Disability and trauma? Disability and abuse?

The short answer is yes: extra medical needs — even in “the richest country on Earth” — are strongly correlated to many other negative indicators.

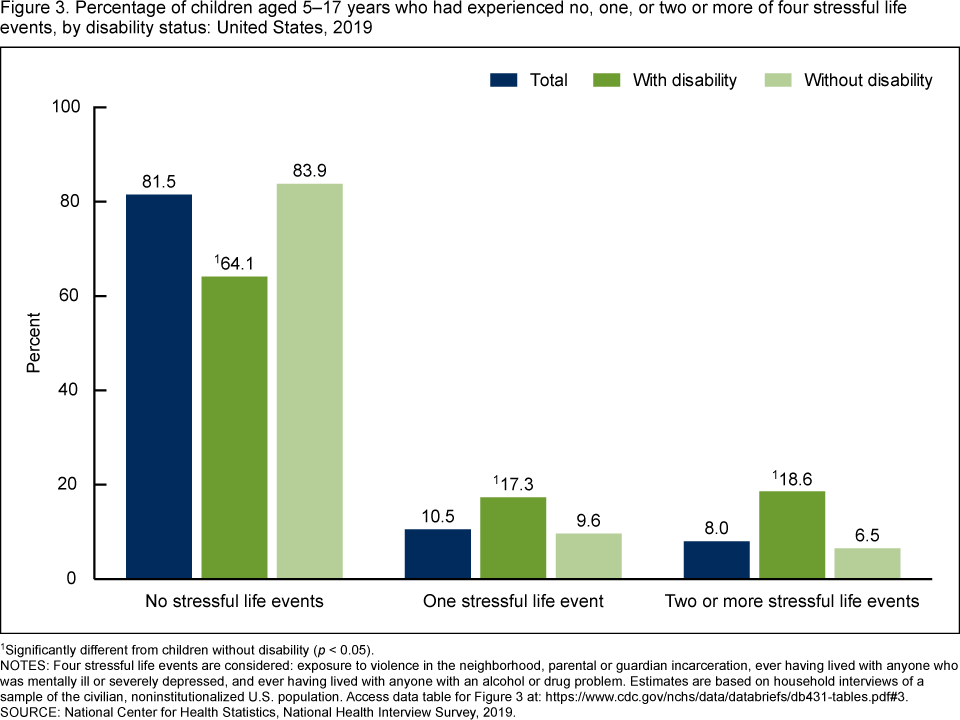

Last month, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found more: Disability and childhood experiences of four different life stressors. These were: growing up around violence, crime, substance abuse and mental illness, including severe depression.

According to the study, disabled children ages 5-17 were three times more likely to be victims of or witness to violence than children without disabilities (17.2 percent compared to 5.3 percent).

These children were also three times more likely to have lived with someone who had a mental illness or severe depression (21.6 percent versus 7.5 percent), or a drug or alcohol abuse problem (17.6 percent versus 8.6 percent).

Disabled children were also much more likely than children without disabilities to have a parent or guardian go to jail (12.7 percent compared to 5.6 percent).

In all, about one in three children with disabilities in the study experienced one or more of these stressful life events — and about half of those had experienced two or more of them. For children without disabilities, the ratio is closer to one in six.

The National Center for Health Statistics, which conducted the study using parent/guardian survey results, noted that there is a lot of research on the ties between these stressful life events and other identifiers — such as race and income level — but not disability.

“Understanding patterns of adverse experiences among children with disabilities can inform policy to support these children and promote their health and full inclusion in society,” researchers concluded.

Research like this is great at proving links between different sets of facts. What it isn’t great at is providing its context. For that, we must zoom out. Disabled children aren’t putting themselves in these situations, so who is?

Parents.

Parents of disabled children are not often studied either. But though we must speculate, it’s not difficult logic to follow. If we hold all other variables equal— income, opportunity, health, happiness — does giving birth to a child with a medical condition suddenly impact a parent’s decision-making power? Does a mother look at her brain-injured preemie in the NICU and say: “You know what, I think I’ll move to a neighborhood with more violence”?

Clearly not.

Childhood disability doesn’t make a parent more likely to make bad choices, it makes it more likely that a parent has only bad choices to pick from. As we’ve discussed, having a child with a disability usually means both parents cannot work, cannot sleep, are traumatized and are attempting to juggle dozens of different medical, social services and school personnel.

I am among the luckier such parents, but I’ve seen enough of the despair in medical mamas’ eyes to guess how disabled children are 2-3 times more likely to grow up around violence, substance abuse, crime and severe depression.

Correlation is not causation, of course. But I do wonder about the interplay between these two realities, especially as the researchers’ definition of disability included crippling levels of anxiety. Having a child with a disability is stressful, for all the reasons I mention each Sunday. But having stressors in one’s life also makes it more likely to have a child with a disability. It is no surprise to me at all that the health and stress of children are linked to the health and stress of their parents.

I want to see more research on why disability is an indicator and what we can do to ensure that more families raising disabled children have the resources they need to provide safety, health and happiness for their children.

The compassion is there — I see it regularly in my community. People care about disabled kids! But the disconnect happens when we transform that compassion into overly complex government systems and mirages of support.

Now that we know that at least a third of disabled children grow up in these sorts of stressful environments, can we stop giving those parents the most amount of work to do? More school forms to fill out, more program requirements to meet, more medical appointments to coordinate, more evaluators to satisfy, more insurance battles to fight.

We must simplify services, especially for these families. We must remove barriers to access for children already dealing with more trauma than average.

I’m not naïve. I know that there are bad parents out there who are simply dangerous to their children. We also must fix our broken foster care systems and overwhelmed child protection agencies to get any children out of these harmful situations. But it is a fact that people often make better choices when they have the resources and opportunities to do so. We must improve the lot of parents so that home life for so many disabled kids never devolves into violence, crime, substance abuse and depression.

Setting up our political structures any other way is to doom our society’s most vulnerable children to even more suffering.

Medical Motherhood’s news round up

Snippets of news and opinion from outlets around the world.

• From ABC News (Australia): “Kmart boosting 'visibility' of children with disabilities through inclusive doll range”

Clinical Psychologist Suzanne Midford said inclusive toys were very important for children who have a disability.

"For a vision-impaired child to see themselves represented by a doll with a guide dog or a cane, or if a child is living with Down syndrome, all these representations can be affirming for that child," she said.

[…]"Research shows that inclusiveness results in greater self-confidence and belonging for disabled children and disabled adults," she said.

"Disability representation in toys is extremely important as previously it wasn't as visible and, to some degree, was non-existent.”

• From The LA Times: “‘I don’t have a life’: Parents struggle to get home nurses for medically fragile kids”

“I’m just so desperate for a break. Just a breather so I can do simple things like cook breakfast, go to the bathroom, shower,” said [Mia] Suarez, a mother of three in Palmdale. “I can’t leave her alone. She likes to pull out her trach” — the breathing tube surgically inserted into her windpipe. “I’m just trying to keep my daughter alive.”

Families in California have long struggled to get nursing care at home for medically fragile children. Even after doctors have deemed home care necessary to keep their kids healthy and safe, many Californians have been unable to secure enough nurses to fill their allocated hours.

Parents and advocates say that, despite efforts to tackle the problem before the pandemic, it has persisted with the arrival of COVID-19. Home health agencies say it has been harder to hang on to nurses when other businesses are recruiting them to handle new demands tied to the coronavirus, including administering tests and vaccines.

“COVID didn’t create a problem that wasn’t there,” said Jennifer McLelland, a member of the advocacy group Little Lobbyists. “COVID just made everything worse.”

• From Newsworks: “The Sun wins £48 million pledge for thousands of disabled children in campaign victory”

The Sun’s ‘Give It Back’ campaign [— a partnership with a coalition of UK charities —] has been urging the government to give back the annual funding cut from hundreds of thousands of families, which rose to £573 million last year.

£30 million will be given to councils for 10,000 additional respite places starting from April. The remaining £18 million will be put into the supported internship programme.

Medical Motherhood is a weekly newsletter dedicated to the experience of raising disabled children.

Get it delivered to your inbox each Sunday morning or give a gift subscription. Subscriptions are free, with optional tiers of support. Thank you.

Follow Medical Motherhood on Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Spotify, or Instagram or, visit the Medical Motherhood merchandise store to get a T-shirt or mug proclaiming your status as a “medical mama” or “medical papa.”

Do you have a question about raising disabled kids that no one seems to be able to answer? Ask me and it may become a future issue.

Share this post