“I like it. Good job.” — Oscar Triplett, 9, about the March 24 rally

As I drove back from the Family Caregivers Car Caravan at the Capitol in Salem last Thursday, I was struck by the depth of feeling from so many of the people I spoke with there. The love between parents and young children is a world-changing force.

Watch a video of the arrival of the caravan at the Human Services building: https://www.facebook.com/shastakm/videos/501086394888524

In the depths of despair, what do any of us say? “I want my mommy,” right? Even if our relationship with our mother is complicated, we have all known the original safety of a womb.

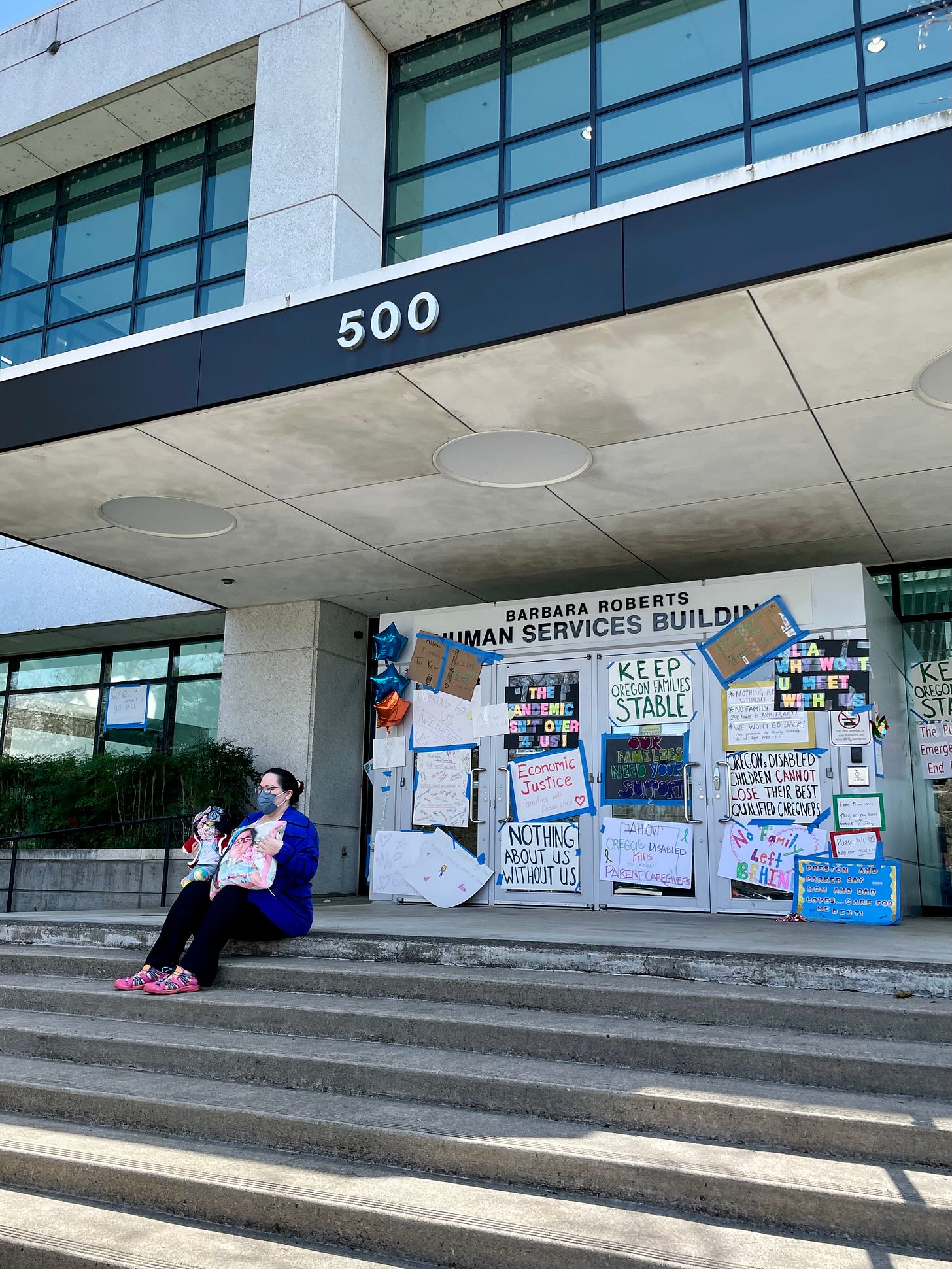

Children — many too young to fully grasp the economic consequences of these policies — came out with their parents and caregivers and friends to ask Oregon to make paying parent-caregivers permanent. This has been a temporary option in the state due to an exception granted during the COVID-19 public health emergency. The Oregon Office of Developmental Disabilities Services recently announced that it would explore options for a permanent program but was vague on the details.

Supporters — like me — want parents to have a seat at the table when such a permanent program is being devised.

Ideally, the children themselves would be advocating for their own needs, but we parents often find we need to advocate for them until they have enough personal agency.

My 11-year-old twins came down and participated in their own way — the loud noises were a bit of a sensory overwhelm but they stayed in their safe car cocoon and loved the energetic atmosphere.

I have explained the issues to them as best I can — that we love our awesome caregivers but they can’t always be around, so when they can’t it would be nice for mama to get those hours so she can feel like she’s contributing — and to buy the stuff we need to survive and thrive.

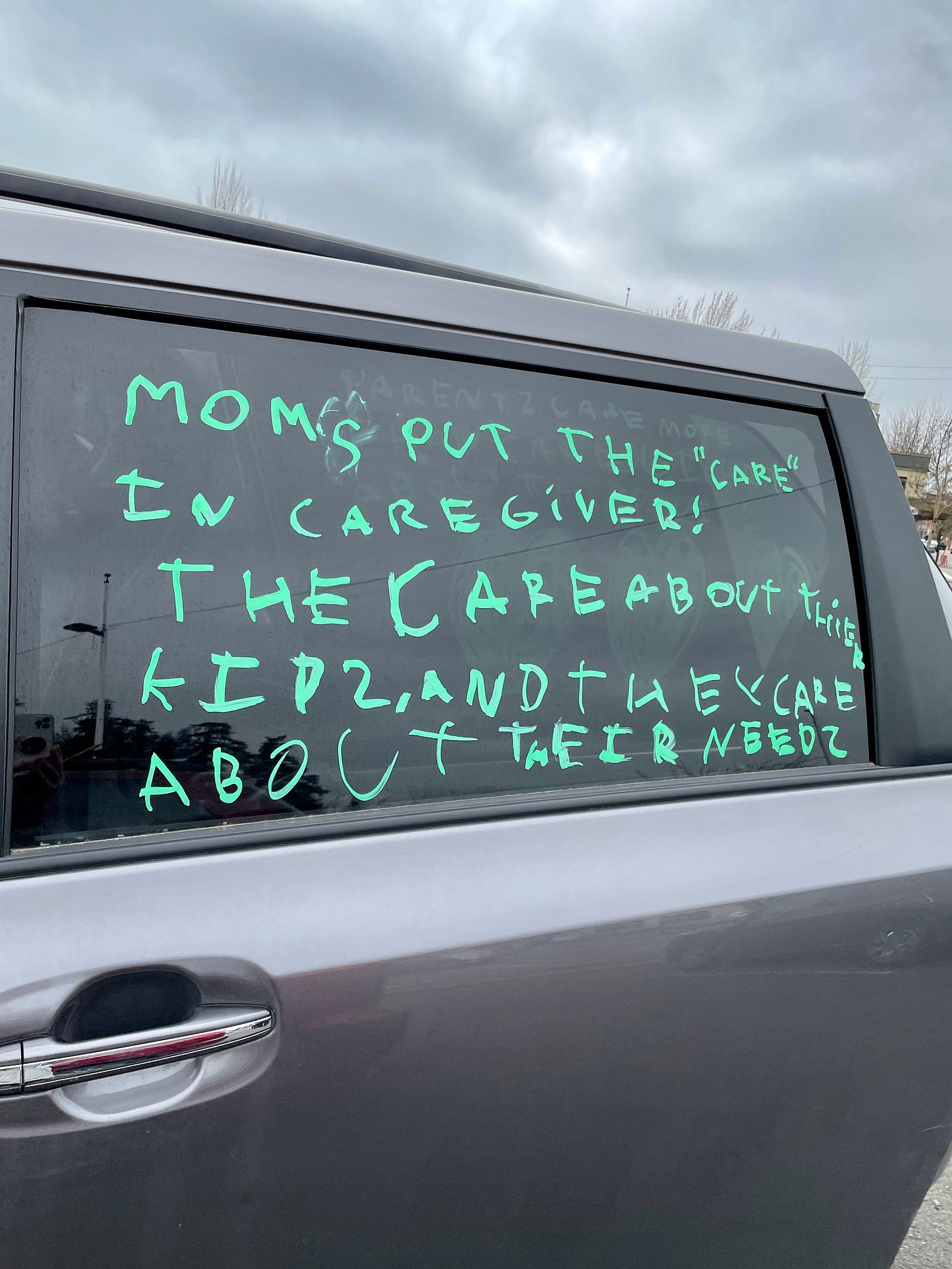

That day, I gave them crayons and poster board and prompted them with a list of slogans they could write if they wanted. But they surprised me.

I thought Mack* would select “A person’s a person, no matter how small,” a quote from his current favorite author, Dr. Seuss. But he chose: “The health emergency never ends for us.” It’s true — COVID-19 was just a variation on a theme for many families with medically complex kids. And, the current labor shortage is particularly acute in the health fields — there are very few caregivers around to employ.

Jasper* skipped my list entirely. He drew a house with a mother and baby and wrote: “Do it for them.” Then, he wrote in bold letters on the side of the car: “Moms put the ‘care’ in caregiver! They care about their kids and they care about their needs.”

At the last minute, Mack surprised me again and said that he wanted to write on the car that other states have this as an option, so I wrote that for him, too.

I tell you all this so you know where my family stands. I wrestle a lot with what political activity I’m “allowed” to do and still call myself a journalist. I used to scoff at people — “citizen journalists” — who would cover protests they so clearly agreed with instead of acting impartially. But the world is ending, the stories I’ve heard have broken my heart, no one else I know of covered this rally, so I can’t bring myself to play a role for the sake of a few imaginary critics. At least on this issue, transparency will have to suffice in the place of objectivity.

As I’ve made clear in previous issues of this newsletter, I definitely have an opinion about paying parent-caregivers — one acquired through a decade of personal experience, three years of research and dozens of conversations. I welcome a conversation with anyone who disagrees, so please reach out.

So, I bore witness as families of disabled children caravanned around the Capitol, honking and shouting, and ended at the Barbara Roberts Human Services building, home to the Department of Human Services and ODDS. With balloons and signs — which they then taped to the building’s front doors — 24 cars full of people asked their voices to be heard. Families say the temporary allowance for parent-caregivers has improved their children’s health and stability in dramatic ways.

Mick Stevens, a Tigard resident who was profiled in this piece in The Lund Report, came down to protest in Salem with his 12-year-old daughter, Jillian. Stevens has been her full-time caregiver almost all of her life out of necessity.

“I think paying the parents, you’re buying the best caregivers for the money,” he said. Stevens added that Jillian has gained skills and experiences that she wouldn’t have gotten with an inconsistent patchwork of caregivers.

Alicia Bodine drove from Dallas, Ore., with her mom and daughter. Bodine cannot afford to work due to Zoë’s needs, so she has to live with her mom — who is allowed to be a paid caregiver, while Bodine cannot. Bodine said she knows that people will criticize her by saying she chose to have a kid and shouldn’t need government support. “It doesn’t matter, because I know that I’m not a lazy person.”

Mellani Calvin, whom longtime readers will recall I spoke with for this piece on social security, made the trip down from Portland. As head of a nonprofit that helps people apply for social security disability benefits, she says that process is still enormously complicated and has even gotten worse since COVID-19. “Families should not have to work so hard to get what they need,” Calvin said.

Several people told me they couldn’t make it due to last-minute medical emergencies with their children or their ongoing 24-7 care needs. Gabriel Triplett, the rally’s lead organizer, acknowledged that in his kick-off speech.

“There are plenty of people throughout Oregon who can’t make it. Because even though they are getting paid to take care of their kids, they are the only one there. They’ve got nobody else,” Triplett said. “We’ve got plenty of people who couldn’t make it today but we fight for them.”

Triplett’s own children couldn’t come either. Oscar, 9, spoke with me over Zoom using a communication device he operates with his eyes. “One good thing about my parents being home is that I get to spend more time with them. I can’t think of anything bad about it,” he said.

Belen Molina had to call 9-1-1 the night before for her 2-year-old medically fragile daughter, but still managed to make the rally after she got her airway cleared with a suction machine.

“How amazing would it be if I could have the resources for what she needs?” Molina said. “It would mean we could get her more of the expensive things she needs and I would know that she’s always taken care of.” The mother of two disabled children is not currently paid because her daughter’s hours are under the limit of the temporary program.

Sydney McIntosh, who has been a paid caregiver for a decade, said she also supports parents being able to do what she does. “I think COVID has made it really difficult to trust people outside your bubble,” McIntosh said. She added that she had to make a lot of personal sacrifices during the pandemic in order to make sure her clients stayed safe, like social distancing, masking and isolating, even when not required by law. “That’s not something everyone is prepared to do.”

She added that not all families will chose to use the hours to pay a parent, “but it’s important to have the option.”

Calli Ross came from Sherwood on behalf of her 7-year-old son, who has end-stage heart and lung disease. She said under this program her husband no longer has to work two jobs to pay the bills. Ross said it is impossible to fill the 540 hours a month of nursing care her son needs. Except for 18 hours a week, the rest of the 24-7 job falls to her and her husband. Under the temporary program, they have paid off medical debt and bought new medical equipment. “Everything we’re making we’re putting back into my child,” Ross said.

Dr. Satya Chandragiri, a psychiatrist at Salem Health hospital and a school board member for the Salem-Kaizer School District, wandered into the protest and thought it was a great idea. He said he frequently sees patients in his practice who are so completely overwhelmed by the hoops they have to jump through in addition to their child’s extra needs that they don’t end up getting any government support for their kids.

“It’s not just the child that has a disability, it’s the entire family that struggles,” he said. “Even if they have eligibility, getting into the developmental disabilities system is almost impossible, honestly.”

Chandragiri said children can struggle with strangers coming to help them with intimate care needs and have trauma reactions. “I think family are the best caregivers,” he said.

Chandragiri also said he was impressed that so many people could even come to the rally because usually care needs in this population are so unrelenting.

Triplett, the rally organizer, said the temporary policy had given struggling families just enough breathing room to organize for what they needed.

“We need to make this permanent so that we can continue to fight.” And, he added: “We’re out here today because the NICUs across the state are filled with brand new parents who don’t know yet how important this policy will be but will need it nonetheless very soon.”

*Not their real names.

Medical Motherhood’s news round up

Snippets of news and opinion from outlets around the world. Click the links for the full story.

• From Science Daily: “One in three children with disabilities globally have experienced violence in their lifetimes, study finds”

Children and adolescents (aged 0-18 years) with disabilities experience physical, sexual, and emotional violence, and neglect at considerably higher rates than those without disability, despite advances in awareness and policy in recent years. This is according to a systematic review of research involving more than 16 million young people from 25 countries conducted between 1990 and 2020. The study provides the most comprehensive picture of the violence experienced by children with disabilities around the world. The findings are published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health.

[…] Analysis of data from 92 studies looking at prevalence found that the overall rates of violence varied by disability and were slightly higher among children with mental disorders (34 percent) and cognitive or learning disabilities (33 percent) than for children with sensory impairments (27 percent), physical or mobility limitations (26 percent), and chronic diseases (21 percent).

The most commonly reported types of violence were emotional and physical, experienced by about one in three children and adolescents with disabilities. The estimates suggest that one in five children with disabilities experience neglect and one in ten have experienced sexual violence.

• From the AP News: “Judge sides with 12 disabled kids seeking masks in schools”

RICHMOND, Va. (AP) — A federal judge has ruled that an executive order and new Virginia law allowing parents to opt their children out of classroom COVID-19 mask mandates cannot prevent 12 vulnerable students from seeking a “reasonable modification” that could include a requirement that their classmates wear masks.

• From AP News: “US judge upholds ‘need review’ for child care service”

The suit, filed last year, said Ursula Newell-Davis wanted to run a business providing “respite” services to disabled or challenged children whose parents can’t be with them around the clock.

Davis’s suit challenged a requirement that she go through a “Facility Need Review” to prove that the business was needed in her area before she could get a license to operate. The lawsuit said the requirement was a legal hurdle designed to protect existing care providers from competition.

U.S. District Judge Nannette Jolivette Brown in New Orleans rejected the suit’s arguments in a 30-page ruling.

Among her reasons, Brown found that the Facility Need Review rule appeared to serve the public interest by making sure the state focuses regulatory resources where they are needed. She said arguments in the lawsuit that the Facility Need Review drives up the cost of care while reducing access weren’t supported. The judge also said that if a more effective way of meeting the state’s regulatory goals can be found, “that is an issue for the legislature, not this Court, to rectify.”

Medical Motherhood is a weekly newsletter examining the policies and practices in raising disabled children.

Get it delivered to your inbox each Sunday morning or give a gift subscription. Subscriptions are free, with optional tiers of support. Thank you to our paid subscribers!

Follow Medical Motherhood on Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or Instagram or, visit the Medical Motherhood merchandise store to get a T-shirt or mug proclaiming your status as a “medical mama” or “medical papa.”

Do you have a question about raising disabled kids that no one seems to be able to answer? Ask me and it may become a future issue.

Share this post