Pediatricians Urge Better Support for Families Shouldering Home Care for Disabled Children

Plus: MIT accepts first nonspeaking student; Trump budget bill makes permanent ABLE savings account flexibilities

The American Academy of Pediatrics published a new clinical report on home health care for children, adolescents, and young adults with “complex medical needs.” While there are an estimated 15 million American children with some sort of disability or chronic health condition, children with medical complexity are the subset of the population with multiple overlapping conditions or a daily dependence on health technology like g-tubes and ventilators.

Released Aug. 25 and appearing in the September issue of Pediatrics, the report validates what many parents like me already know: keeping kids at home is best. But making that work requires real systems of support. Happily, I believe this is the first time an AAP report has specifically called out a recommendation for paid family caregiving.

Beyond that, what struck me most in the comprehensive recommendations was a strong emphasis on legitimizing telehealth and in-home therapies. The report also had a repeated and detailed descriptions of what a “medical home” should look like, causing me to look into the definition of this type of care. Since 2002, the AAP has recommended a “medical home” model for children with medical complexity (CMC). You can find one of these by searching for a certified Patient-Centered Primary Care Home or PCPCH. These clinics offer care coordinators, enhanced access like same-day or after-hours appointments and family-centered care. Regardless, all pediatricians of children with complex needs are advised to schedule these patients for longer appointments because “acute issues often crowd out much-needed time for routine pediatric care,” and to ensure accommodations like larger exam rooms and accessible tables for them.

The report also calls out the hidden workforce behind this care: parents. As it states: “It is important that the primary coordinator of care be identified; parents often assume this role without adequate support and spend hours on care coordination, which can result in forgone medical care, lost wages, and less family time.”

Ain’t that the truth.

It also says: “Family caregivers have the most insight on the realities of care and services at home and creating a trusting relationship is critical to success.”

Can someone turn that into a T-shirt I can wear to my next appointment?

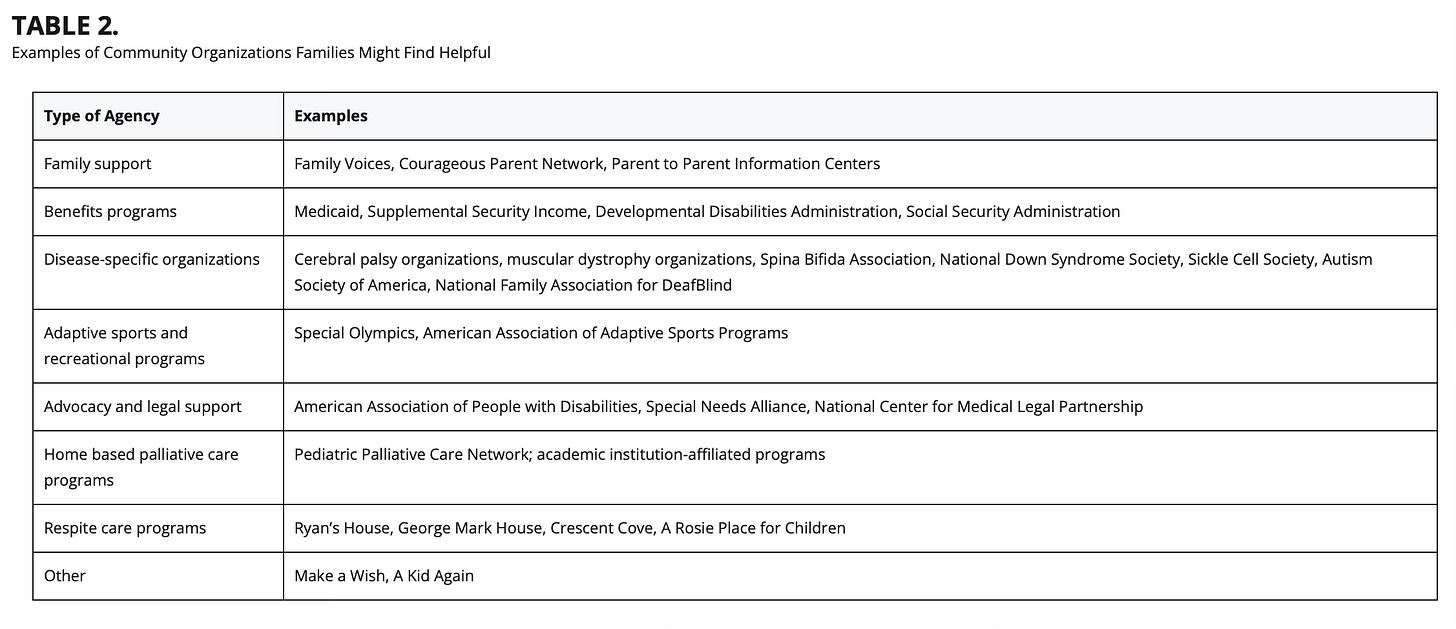

While in 2024, there was advocacy guidance released to chapters on the need to advocate for paid family caregiver programs, this report is the first time I’ve seen an explicit public recognition of the need for paid parent caregiving models from the organization. The AAP urges doctors advocate for the expansion or implementation of these programs. “Pediatric health care providers can help advocate for paid family caregiving, as well as increased payments in order to improve the situation for families.” Pediatricians should know what options exist in their states and urge families to look into home care programs or paid caregiver programs in order to “minimize the gaps” in the home health workforce.

Disability affects the entire family system. The report encourages doctors to consider individual and cultural expectations in crafting treatment plans. One-size-fits-all models don’t work. And the report also acknowledges the impact on siblings. Pediatricians are encouraged to monitor “well” brothers and sisters of CMC for stress or overlooked medical needs.

The report also contains sobering data on rehospitalizations. Among CMC with home nursing, one study found that after discharge 18 percent were readmitted within 30 days, 62 percent within a year, and 87 percent within two years. The most common reasons were infection (41 percent) and device complications (10 percent).

Beyond caregiving, the report affirms the need for fair compensation for physicians, including for all that paperwork that schools, social services and other systems want from them. It points out that a “major disincentive in the current system of care is the lack of physician compensation for time invested in phone management, care coordination, completion of home health care orders and recertifications, management of medication refills, and letters of medical necessity.” The AAP also calls for sustainable funding of telehealth and remote monitoring “to continue to offer this type of care to families,” and even suggests that “home visits by pediatric health care providers can offer a safe and efficient alternative to traditional office visits.” How much better would it be not to have to spend half the day going to an appointment?!

Finally, the report affirms the legal bottom line: “CMC are entitled to home health care services, and states are mandated to provide this service to allow these children to transition safely to their homes and communities.”

That’s not just a suggestion — it’s the law.

For medical mamas like me, these words matter. They validate what we’ve lived, and they push the medical system to see us not as extras in the story of our children’s health, but as essential partners whose insight, labor, and advocacy keep kids alive at home.

Medical Motherhood’s news round up

Snippets of news and opinion from outlets around the world. Click the links for the full story.

• From WBUR via IdeaStream: “Non-speaking teen with autism — once thought to be intellectually disabled — accepted at MIT”

When Viraj Dhanda begins his freshman year at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he’ll be the university’s first-ever non-speaking student with autism.

Diagnosed with autism at age 2, Viraj Dhanda was mistakenly thought to be intellectually disabled for the first 14 years of his life, his father, Sumit Dhanda, said. Viraj Dhanda also has apraxia, a neurological condition that limits muscle movements and motor skills. The condition is not uncommon among people on the autism spectrum. Viraj Dhanda communicates using text-to-speech assistive technology, typing on his tablet with one thumb.

“I hated being labeled mentally disabled. People thought I was behavioral because I flopped on the floor, used my body to communicate, but what was I supposed to do?” Viraj Dhanda said. “I couldn’t sign or speak, and I was desperate for the world to know that I had a fully functional brain.”

[…]Viraj Dhanda started using [a] communication device to request his favorite TV shows, then a breakthrough came right before his 13th birthday when he was watching a show called “Super Why!,” where animated characters spell out words. […]“Before it gets spelled on the screen by the superhero, he says the letters that he can […A] light bulb goes on in me,” [dad] Sumit Dhanda said. “Oh my God. We had this entirely misdiagnosed.”

[…]“Speech and language are two different centers of the brain. So, you can have language without having speech because speech is a motor function,” Sumit Dhanda said, “and this is where I think the therapist community at large often fails these children.”

Viraj Dhanda started using a large letter board, pointing to individual letters to spell out his thoughts. With the help of his father, he then started working on smaller and smaller devices until he found success on a tablet that could verbalize his thoughts.

[…]By the time Viraj Dhanda was reevaluated, he was ready for college-level math courses and enrolled at Fusion Academy in Newton, Massachusetts, where he flourished with personalized lesson plans and one-on-one instruction.

“ It felt liberating,” Viraj Dhanda said. “The simple dignity of being able to speak was enough for me.”[…]

• From DisabilityScoop: “ABLE Account Rules Updated As Bigger Change Looms”

[…]Tucked inside President Donald Trump’s signature “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” which passed in July, are several provisions affecting ABLE accounts.

Established under a 2014 federal law, the accounts offer people with disabilities the opportunity to save up to $100,000 without sacrificing eligibility for Social Security and other government benefits. Medicaid can be retained no matter how much is in the accounts.

[…]A handful of rules governing how the accounts are used were set to expire at the end of this year, but the recent legislation now makes them permanent. That includes the option for ABLE account holders who are employed to save extra money in their accounts if they don’t participate in an employer-sponsored retirement plan as well as the ability to roll over funds from a traditional 529 college savings plan into an ABLE account. That provision is designed to help families that set up college savings plans before knowing their child had a disability.

In addition, the recent legislation ensures that ABLE contributions remain eligible for what’s known as the Saver’s Credit.

The changes will bring “increased confidence in using ABLE accounts,” according to Paul Curley of ISS Market Intelligence, which tracks ABLE account trends.

As of the end of June, there were 213,855 ABLE accounts open with $2.68 billion in assets, according to the firm.[…]

Not sure about ABLE accounts and why you should get one? Read more about their benefits in this past issue of Medical Motherhood:

Medical Motherhood brings you quality news and information each Sunday for raising disabled and neurodivergent children. Get it delivered to your inbox each week or give a gift subscription. Subscriptions are free, with optional tiers of support. Our paid subscribers make this work possible! Not ready to subscribe but like what you read here? Buy me a coffee.

Follow Medical Motherhood on Facebook, Bluesky, X, TikTok, Instagram or Pinterest. Visit the Medical Motherhood merchandise store.