“As an influential artist I’m dedicated to being part of the change I’ve been waiting to see in the world.” — Lizzo

Language evolves and the disabled community is not a monolith. There are different and changing opinions on what are — and are not — appropriate ways to refer to the experience of being physically or mentally different than nondisabled people.

In the recent New York Times essay “‘Is that Ableist?’ Good question.” blind writer and performer M. Leona Godin wrote about her experience as a Gen Xer speaking to two younger activist friends. Her exclamations that she felt “dumb” or “stupid” were met with admonishments of being “ableist.”

“I began to sense a generational divide. The word “ableist” was definitely not one I heard as a kid. And while today I have as much disability pride and blind pride as anyone I know, I get stuck sometimes on the ableist language — and humor — that I grew up with as a Gen Xer.”

Having been in the disability rights space for more than a decade, I was surprised to discover that ableism — the disability corollary to racism, sexism and other prejudice— is still a niche concept.

Google Trends is a way that anyone can see how popular different search terms are and how that has changed over time. The data go back to 2004.

“Ableism” as a search term is relatively rare but has grown substantially in popularity since May 2020. There was also a massive spike in searches the week of June 11 to 18 of this year. That was when pop artist Lizzo released a song with the lyric “spaz” — a term with derogatory roots that refer to the tight, spastic muscles some people with cerebral palsy experience. (After listening to fans, Lizzo rereleased the song without the offending lyric just days later.)

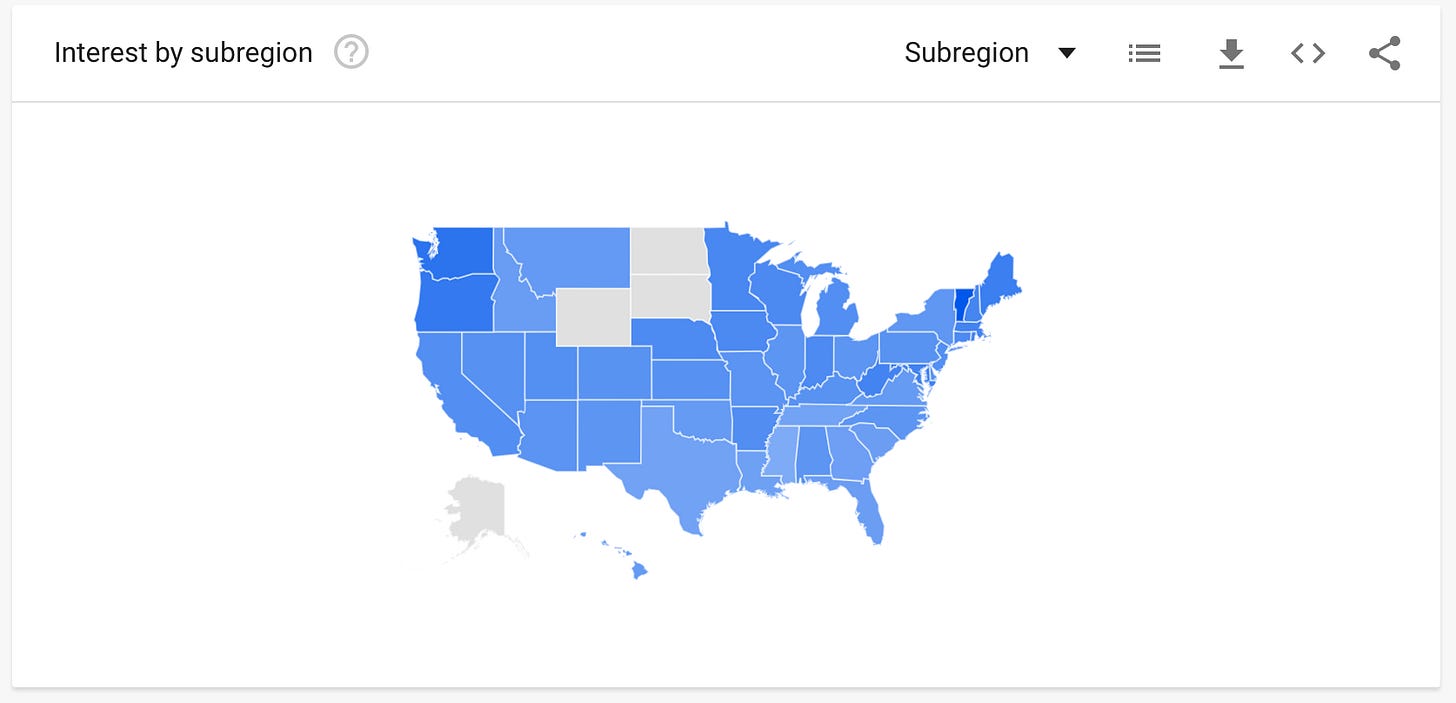

But — during the course of the last 18 years — “ableism” is still practically un-searched-for in four states: Alaska, Wyoming, North Dakota and South Dakota. People in Vermont have searched for it the most, followed by Washington and my home state of Oregon. Most people seem to be looking for its definition and meaning.

This is part of how language evolves. New words grow in popularity and old ones fall away. There is an entire campaign, for example, to get people to stop saying the “r-word.” Interestingly — as I noted in this post last year — “retard,” “handicapped,” and “moron” were orginally introduced as more polite alternatives that became offensive over time. “Cripple” has had the reverse fortune: it has now been reclaimed by many disabled people.

Many Gen Xers and Boomers may cringe at my use of “disabled people” instead of “people with disabilities.” The debate over “person-first language” and “identity-first language” continues, but the newest trend in most circles seems to be to honor disabled identity by using it first.

“Special needs” is how most people these days refer to disabled children but there is a popular belief in disability rights circles that that is because parents cringe at giving their children a “disabled” label. This message doesn’t appear to be getting through to the mainstream though — the frequency for “special needs” as a search term has stayed steady since 2004. This 2016 study was able to take a longer view and found that the term has gained popularity as a euphemism in books since the 1970s even as “handicapped” sharply declined.

The same study used short character descriptions to determine that when a person is described as having “special needs,” rather than “a disability,” they tend to be viewed more negatively. This was even true among people with a personal connection to disability, like parents of disabled children.

So that is why I no longer use “special needs” to describe my children, nor do I describe myself as a “special needs mom.” In fact, that is the reason I called this publication Medical Motherhood — so that we could start to have new labels for a common experience.

Unflinchingly using the terms “disabled” and “disability” is considered the most respectful terminology today — despite the words’ 16th century roots in the rather barbaric English Poor Laws. So I also looked up the Google trends for those words and found that “disability” is most commonly used as a euphemism not for people but for government aid checks — Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income.

The search term “disabled” isn’t most frequently associated with people either. It is correlated to searches for iPhones and other broken or locked technology. This leads me to wonder if — in 20 years when raised-on-technology Gen Alpha is in charge — that term will be considered disparaging too.

If it is, I hope we all maintain the flexibility of mind and openness of spirit to evolve our language and learn from those most affected.

Want to learn more about this topic? The Nora Project is hosting a 60-minute online webinar on disability history and language for $25 on Aug. 11. A recording will be available if you can’t make the 7:30 p.m. central time.

Medical Motherhood’s news round up

Snippets of news and opinion from outlets around the world. Click the links for the full story.

• From Jezebel: “Celeb Actually Takes Accountability For Problematic Thing”

On Monday, [June 13], disappointed Lizzo fans stormed Twitter to call out the rapper’s use of the ableist word “spaz” (“Do you see this shit? I’m a spaz”) in her song “Grrrls.” And Lizzo’s prompt response should serve as a lesson to all public personalities on how to respond when you do something controversial or inadvertently hurt people.

[…]“Let me make one thing clear:[“ Lizzo posted in a note on Twitter “]I never want to promote derogatory language. As a fat black woman in America, I’ve had many hurtful words used against me so I understand the power words can have (whether intentionally or in my case, unintentionally.) I’m proud to say there’s a new version of girls with a lyric change.”

• From Boston 25 News: “25 Investigates: Kids with developmental disabilities hit hard by mental health crisis”

According to the Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association, 619 patients, including 78 pediatric cases, were boarding in emergency rooms or other medical floors across Massachusetts hospitals as of July 5th.

“It’s going to be important and crucial that we develop a hybrid system of being able to provide in person services and telehealth services to meet the level of challenges that that all of these kids have,” said Dr. David Cochran, director of the CANDO center.

The Worcester facility he runs offers specialized resources for kids with autism spectrum disorders and emotional health struggles on an outpatient basis.

Cochran adds that more community-based centers and mobile crisis teams are a must if the needs of this vulnerable population are to be met.

“Prior to [COVID-19], kids with autism spectrum disorders were nine times more likely to present to an emergency room for psychiatric concerns and six times more likely to need hospitalization than kids without autism,” he said.

[Mom Jennifer] Drohan says families of individuals with developmental disabilities deserve a level playing field.

“We have a responsibility to not just sit by and say this is a broken system,” she said. “We are in grave need of those clinicians that understand the intersection between both disabilities like autism and mental health.”

• From The Wire: “How Children With Special Needs Are Being Left Out of Mainstream Education in India”

Bengaluru: “Nobody accepted my child into a mainstream school,” said Sudha Madhavi, whose child, Raju has epilepsy, autism and a learning disability. She had to teach her son at home all by herself.

“I am alone fighting for my child,” she told The Wire. Teachers have said that he can’t sit in one place, that he has difficulty learning what is being taught and that he disturbs others. “What can I do? I have to accept the social norms, right?”

While Raju eventually managed to study in a vocational school, not every child with a disability is admitted to mainstream educational institutions. In fact, out of 78.64 lakh [— or what Americans would call 7,864,000 —] children with disability in India, three-fourths of those aged five years don’t attend any educational institution, according to a 2019 UNESCO report.

Additionally, 12% of the children with disability have dropped out of school and 27% of children with disability have never attended any educational institution.

Medical Motherhood is a weekly newsletter giving those raising disabled children the news and information they need to navigate complex systems. Get it delivered to your inbox each Sunday morning or give a gift subscription. Subscriptions are free, with optional tiers of support. Thank you to our paid subscribers!

Follow Medical Motherhood on Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or Instagram or, visit the Medical Motherhood merchandise store to get a T-shirt or mug proclaiming your status as a “medical mama” or “medical papa.”

Do you have a question about raising disabled kids that no one seems to be able to answer? Ask me and it may become a future issue.