The Hardest Jobs, the Most Hoops: How Medicaid Could Add Even More Complexity

Plus: Disabled kids are at higher risk of suicide but rarely get screened; and Trisomy 18 kids are living longer than previously thought possible, thanks to medical mamas' expert care

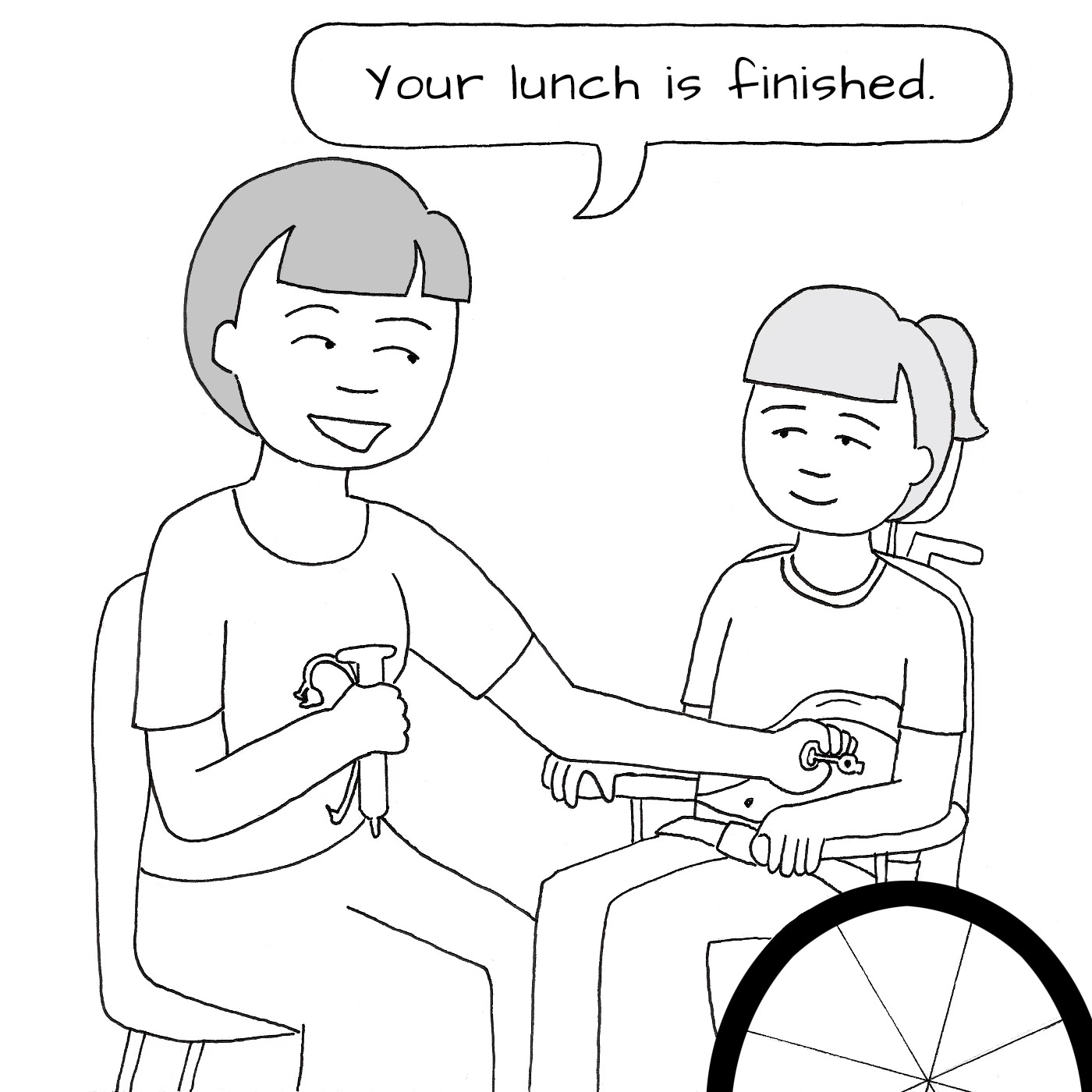

I’m trying something new this week with Lenore Eklund’s Where Is the Manual for This?! comic. I realized that mobile users might have trouble seeing the images so I’m putting each of the panels here. What do you think? Do you like this better? Should we go back to the four-panel view? Let me know in the comments or reply to this email.

Sign me up for the g-tube plan

With having identical twins who are both picky eaters, it has definitely crossed my mind a time or two how much easier it would be if they both had g-tubes! It sure would be nice to bypass our tastebuds sometimes to get all those healthy foods in.

In the news…

I was interviewed last month for this by The Oregonian and impressed at how quickly reporter Kristine de Leon’s grasped Medicaid policy from our first conversation to this finished product. This section is specific to my home state but is also a great summary of how the One Big Beautiful Bill Act’s impacts will roll out across the nation.

Vincent Mor, professor of health services, policy and practice at Brown University, said Oregon has invested heavily over the last 25 years to expand its home and community based services to support more people in their homes. He said studies have found that arrangement lowers costs while allowing for more personalized services.

But if funding cuts force a choice, the Oregon Health Plan must go with required nursing home care, even if the state pays less for in-home and community care. Following similar federal funding rollbacks after the Great Recession, Oregon cut its per-person spending on home care by nearly half.

The recent spending law imposes new limits on federal matching dollars that, when they take effect in 2028, could cost the state more than $10 billion over 10 years.

Dr. Ben Sommers, a physician and health economist at Harvard University, said that because states — unlike the federal government — are required to balance their budgets, they will have to “find other ways to save money.”

“How do you save money in Medicaid? You can cover fewer people, cover fewer benefits, or pay doctors and hospitals less,” he said.

Take a read of the whole piece at this link: Oregon embraced expanded Medicaid benefits. Federal cuts could put them on the chopping block.

My favorite quote isn’t one of mine, but from the mom at the center of the story. Tiffany George said: “I don’t think people understand how terrifying it is to be responsible for keeping your child alive, and at the same time have to jump through hoops to hold on to the help that makes that possible.”

It’s crazy, isn’t it? That we give the hardest jobs and the most bureaucratic busy work to the people in our society who are the least able to jump through more hoops.

Medical Motherhood’s news round up

Snippets of news and opinion from outlets around the world. Click the links for the full story.

• From New York Times Magazine: “Noah Is Still Here”

Dr. Jacqueline Vidosh returned home from her clinic one afternoon late last year and hustled into the bedroom of her youngest child, Noah. She began troubleshooting with his home health care nurse, trying to figure out why his oxygen levels were lower than normal. Had Noah caught the cold going around their house in San Antonio? Jacqueline, an obstetrician, peered at Noah’s vital signs on a monitor as she absently petted the family’s Doberman.

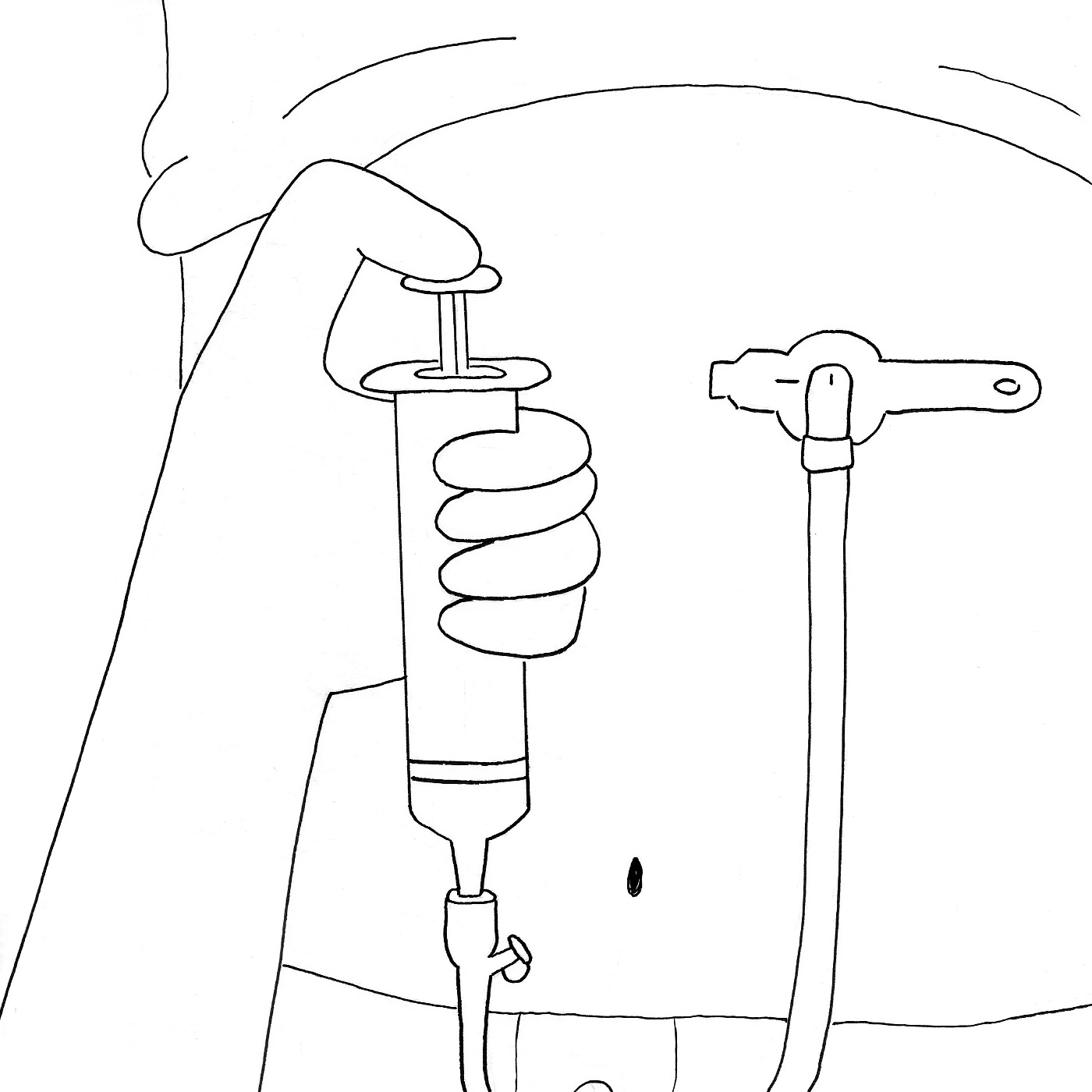

[…]Jacqueline emptied a cup of saline solution into the chamber of a nebulizer and attached it to the ventilator that Noah uses to breathe. As he began inhaling the moist, vaporized air, Jacqueline wrapped a vest around him and flipped a switch that caused it to inflate and deflate rapidly, beating against Noah’s chest to loosen any mucus that might be blocking his airways. Jacqueline used a syringe to check for residual formula in Noah’s stomach through his gastrostomy, a surgical opening in his abdomen. She then used a machine to induce coughing and employed a suction device to clear out respiratory secretions through Noah’s tracheostomy, a surgical opening in his neck. The process took about 20 minutes. Noah’s oxygen levels improved.

[…]Earlier that evening, a patient who was 21 weeks pregnant had texted Jacqueline asking to talk. The woman’s fetus had the same rare chromosomal diagnosis as Noah, trisomy 18, also known as Edwards syndrome. […]The woman explained that at a prenatal appointment that day, an obstetrician had inquired whether she would want her son’s heart and spine defects to be surgically repaired after he was born. She cried as she told Jacqueline that she needed more information to decide on the operations. She also worried that no surgeon would be willing to perform them.

Trisomy 18 is one of the few conditions in pediatrics for which there is no agreed standard of care. Different hospitals, doctors and surgeons vary in their willingness to offer even basic medical interventions. Some physicians tell pregnant patients what was long believed to be true — that the fetus has a fatal condition — even as newer science shows that some babies can live for years. Parents are often left to battle for information and care, and battle with themselves over whether treatments that might give children a shot at a longer, healthier life, but will not cure their cognitive disability or all their serious medical problems, are more likely to harm than to help.

Despite being a physician, Jacqueline had often felt the need to prove to other doctors “that Noah’s worth my time and effort,” she told the pregnant woman. Few people “have any kind of understanding of what this complexity feels like.”[…]

• From Psychiatric Times: “Suicide Risk Screening for Children With Neurodevelopmental Disabilities: New Insights”

[…]In 2023, the [Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Behavior Risk Survey System] revealed that 20% of high school students seriously considered suicide, 16% planned for suicide, 9% attempted suicide, and 2% were injured in a suicide attempt. Of note, female and LGBTQ+ students were disproportionately affected.4

To address the rising rates of youth suicide, the AAP partnered with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention to generate a guide of best practices for suicide prevention in the “Blueprint for Youth Suicide Prevention.” Part of those recommendations include universal suicide risk screening for children aged 12 and up and screening for kids aged 8 to 11 years when clinically indicated.5 However, it is important to note that youth with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) are often systematically excluded from suicide risk screening protocols, despite clear evidence that they are at risk.

Studies show that children with intellectual disabilities are 2.8 to 4.5 times more likely to have psychiatric comorbidities, and up to 42% of children with NDD report suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Youth with autism, particularly those without intellectual disabilities, face an elevated risk of suicide-related mortality. Factors such as depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and the stress of camouflaging autistic traits contribute to this vulnerability.

[…]To address this, my team implemented a universal suicide risk screening program at Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

[…]Screening is not only feasible but essential, even for children as young as 8 and those with neurodevelopmental disorders. This work underscores the need for inclusive, evidence based approaches to protect some of the most vulnerable members of our communities.

Note to my paid subscribers: I’m sorry, I know my quarterly report is late! It will be in your inboxes next week.

Medical Motherhood brings you quality news and information each Sunday for raising disabled and neurodivergent children. Get it delivered to your inbox each week or give a gift subscription. Subscriptions are free, with optional tiers of support. Our paid subscribers make this work possible! Not ready to subscribe but like what you read here? Buy me a coffee.

Follow Medical Motherhood on Facebook, Bluesky, X, TikTok, Instagram or Pinterest. Visit the Medical Motherhood merchandise store.