Hello to my many new recent subscribers! Medical Motherhood has grown a lot in the last few months, including the addition of a podcast version, so this week, I’ve decided to rerun a popular issue explaining the process and issues in Social Security for disabled kids.

The idea for Social Security started in 1933 as a letter to the editor from a California doctor.

Dr. Francis Townsend came up with the plan for a guaranteed retirement income after watching three elderly women pick through trash for food.

It snowballed rapidly. The core idea was so motivating that in just two years it became a national law.

It started out simple enough: just help people. Give them money. Simple.

Decades later, it is the mess we know today.

Non-retirees who qualify for benefits are extremely poor and the checks are very low. The application process is laborious, lengthy and usually unsuccessful. The resource limits mean Americans with disabilities are often stuck in a poverty trap, unable to ever save or make enough to provide for themselves.

Before I fell through the looking glass into Special Needs World, I, too, had a vague idea that in America we took care of disabled people. That Social Security offered some sort of soft landing for the vulnerable and unfortunate.

I had no idea just how wrong I was.

My personal introduction to the Social Security Administration came in the first six months of my babies’ lives. Over the course of that time, I had 16 social workers (yes, 16, I counted) and many of them advised me to look into SSI to see if we qualified. None of them knew what the requirements were. So one day, in between diapers and doctors’ visits and countless sleepless nights, I finally began the lengthy process. It ended up as yet another wild goose chase.

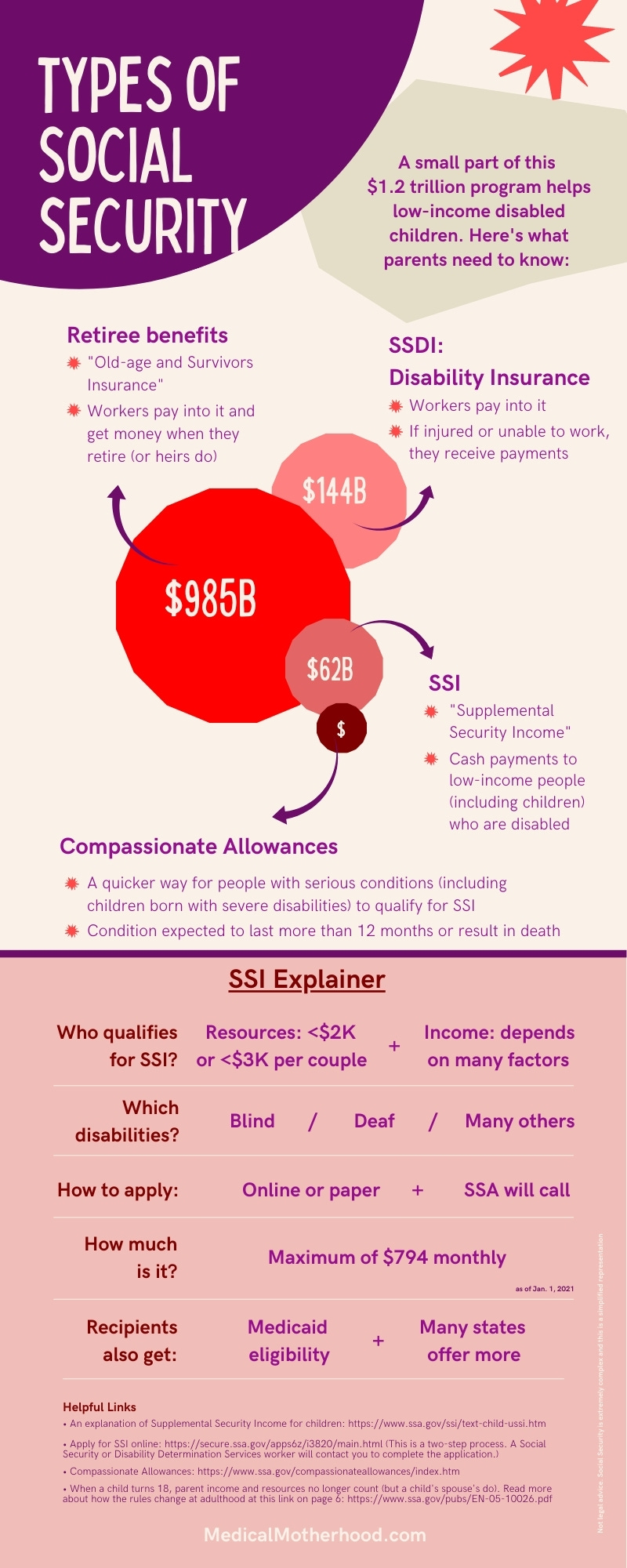

First, you have to understand the incredibly confusing acronyms. The SSI I’m talking about here is Supplemental Security Income. The SSA (Social Security Administration) doles out this money. They also manage the much-more-famous Social Security benefits for retirees and their heirs, called “Old-Age and Survivors Insurance” or “Retirement Insurance Benefit.” This public pension system is what most people mean when they say “social security.”

If that weren’t confusing enough, SSDI (Social Security Disability Insurance) is for workers who become disabled. Disabled children and adults don’t qualify for this if they have never worked in the labor market.

SSI — the program we are talking about here — is paid for out of general tax funds and not the Social Security trust that everyone talks about “running out of money” (though that is debatable).

Applying for SSI starts with a 23-page paper application or you can fill out an online application. Less than half (43.5 percent) of applications for disabled children were approved in 2018 but that’s still a lot better than the just 30.4 percent for adults.

Mellani Calvin is a friend of mine and executive director of a Portland, Ore., nonprofit that helps some of the hardest-hit folks get their benefits. Even as non-lawyer advocates, ASSIST has had a 78 percent success rate with hundreds of clients over their decade in business — more than twice the national average.

Calvin says the key to their success is an avalanche of evidence.

“We just paper the case,” she says. “SSA is not used to families or individuals advocating for themselves, (but) because it’s your claim, you get to send anything you want.”

In other words, Calvin helps people get benefits by preparing like she’s going to court. The average ASSIST application, Calvin says, takes about 25 staff hours plus another 10 hours for the client.

She has her clients’ doctors write detailed letters outlining their functional deficits. This can be difficult because it is unpaid work for the clinicians, but she says those are key. Without detailed letters, Calvin argues SSA staffers (or, rather, their contracted agencies, called Disability Determination Services) essentially “guess” from medical records that often don’t include the pertinent information.

No one from SSA or DDS meets the disabled children before granting or denying benefits. They have a phone call with an overwhelmed caregiver about their financial picture and, at most, ask them to go through yet another doctor’s visit to verify their claim.

SSA’s budget request, however, appears to hint that the agency is aware of its systemic problems. The message to Congress lauds lowering its average decision times from a staggering 605 days in 2017 to an estimated 310 days last year.

The budget request also underscores how costly it is to make people go through the appeals process after a wrongful denial. “Hearings are the most expensive part of the disability process. We must ensure that we make fair, policy-compliant disability decisions supported by the most efficient, modern business processes,” it says.

The SSA is also gearing up to study the barriers to work for disabled adults and children, as well as the barriers to accessing benefits. Disability advocates have long claimed that SSI keeps recipients stuck in a cycle of poverty and even bars them from getting married.

To give you a ballpark idea, a two-parent household with two kids, one of whom is the SSI recipient, can earn up to $53,904 in wages before their SSI check reaches $0. (See a chart in the middle of this webpage.) That may not sound too bad, but there is another limit that is very clear: the disabled child may not live in a household with more than $2,000 in resources, or $3,000 for a couple.

“There is no tolerance for any amount above the resource limits,” SSA regional spokeswoman Shayla Hagberg wrote in an email to Medical Motherhood. (She notes that several types of assets are not counted as resources but most types of savings, a second car or even a life insurance policy are.)

The $2,000 cap ($3,000 for a couple) was passed in 1984 and enacted in 1989. If those limits had just kept up with inflation, they would be $5,565 and $8,347 today.

My family may have qualified under those inflation-adjusted limits when I first called SSA. But we didn’t qualify under the actual limits. Not even when we were on food stamps and living in a tiny 2-bedroom house worth $40,000 less than our mortgage.

So it’s surprising and depressing that even with such a low bar for the amount of savings a family can have on the program, more than 1 million U.S. children receive some amount of SSI — that’s 1.4 percent of all Americans under the age of 18. Seventy percent of those qualify because of a mental condition, like autism or ADHD, as opposed to a physical disability. Children make up almost 13 percent of SSI recipients. (source)

Once a parent gets their child’s application through the gauntlet — or perhaps goes through the even-more-laborious appeals process — what do they get? A maximum benefit of $794, or less than $10,000 per year. (Some states supplement this payment. In Oregon, where I live, they are called “Special Need payments.” They aren’t much.)

That is the maximum amount. Payments are lowered the more income parents have. In April 2021, the average monthly payment to families of disabled children was $694.80.

The entire SSA has a mind-boggling $1.2 trillion budget. SSI alone has a $62.7 billion budget, nearly 8 percent of which ($4.8 billion) is spent on administration.

It’s unclear how much of those SSI payments are for children. But by taking the number of children on SSI here and the average monthly payment here, I get roughly $8.86 billion in annual benefits for these, the poorest and most disabled American children. For comparison, that’s about two-fifths of what the U.S. sends abroad in foreign aid each year.

A simple system, born of compassion. How far Social Security has strayed from that ideal.

Medical Motherhood’s news round up

Snippets of news and opinion from outlets around the world. Click the links for the full story.

• From Yes! Magazine: “Why the Formula Shortage Is Also a Disability Rights Issue”

The baby formula shortage wreaking havoc across the United States is terrifying for any parent who relies on infant formula to feed their child. It’s especially calamitous for babies and children with special health care needs who rely on special prescription formulas that have also been impacted by the supply shortage.

The shortage highlights an ongoing, systemic failure to ensure vulnerable children have secure access to medically necessary, life-supporting products and equipment. Families with healthy infants who had previously never experienced this level of stress over finding a product that should be readily available are now facing a situation that is sadly the status quo for families of children with disabilities.

This shortage—precipitated by a major recall of infant and pediatric formula produced by manufacturer Abbott Nutrition in February—has received major media attention, most of it focused on families who can’t find the over-the-counter Similac baby formula brand. Less attention has been given to the supply crisis in specialty prescription formulas like EleCare and hypoallergenic formulas like Alimentum (both also part of the Abbott recall). These specialized, medically necessary formulas are designed for children with gastrointestinal disabilities who can’t tolerate traditional formula. The shortage of these products affects not only babies, but also children and teens with complex digestive problems and allergies. This includes children fed through a jejunal tube (a feeding tube that bypasses the stomach and feeds the child directly in the small intestine); children with serious allergic conditions, like eosinophilic esophagitis or gastroenteritis; and children with intestinal malformations and malabsorption disorders.

• From CBC in Canada: “Children with disabilities getting inconsistent government support, Alberta auditor general finds”

Alberta families hoping for financial help for their children with disabilities are often at the whim of their caseworker, rather than consistent rules, the province's auditor general has found.

Furthermore, only about one in five caseworkers and supervisors with the Family Support for Children with Disabilities (FSCD) program had completed all mandatory online training. About a third of those who did finish training whizzed through the multi-hour modules in less than five minutes, the auditor's office found from digital data.

The findings could lead to the perception the government is making decisions unfairly, Auditor General Doug Wylie said on Monday.

[…] Wylie's office found plentiful inconsistency within the FSCD program, which paid out $193 million in supports to more than 15,000 families in 2020-21.

FSCD helps families cover the cost of expensive therapies, counselling, clothing and shoes, medications, respite care and other services children need to survive and thrive.

• From The New York Times: “Sabrina’s Parents Love Her. But the Meltdowns Are Too Much.”

In interviews, parents across New York State described the same scenes of fear and helplessness: being attacked by an adolescent child, now bigger and more aggressive than before. The dread that their child might turn on a younger sibling. Their growing helplessness as their child’s self-injuring behavior — relatively common among autistic children — escalates. The emergency room visits when there was nowhere else to go. And their eventual realization that the family home may be the wrong setting for their child.

A father in Brooklyn described his anguish at watching his autistic son smash his head repeatedly against the hardest nearby surface: the wall, the floor, the detachable shower head. A mother in Albany described her daughter’s wild behavior: endless twirling, chewing on walls. Earlier this year, the girl was found in the yard with a broken arm, having either jumped or fallen out of a second-story window.

“One of the glaring weaknesses of the system is there is no real option for families whose children fall into that category,” said Christopher Treiber, an associate executive director at the InterAgency Council of Developmental Disability Agencies.

A half-century ago, many children with autism ended up in notorious state institutions like the Willowbrook State School on Staten Island, where those with developmental disabilities were left untended in filthy wards or strapped to beds.

In the years since these institutions were closed, there has been a clear presumption about what’s best for many children with intellectual or developmental disabilities: They should live at home through childhood, attending special education classes and programs, eventually moving into group homes at some point in adulthood.

And for decades, this policy has kept families intact and provided richer, more connected lives for those with such disabilities. But the presumption can fail a small number of families like the Benedicts.

[…]But gaining admission is a slow and sometimes adversarial process. The government can be reluctant to approve these placements, which can cost more than $300,000 a year — a cost shared by a local school district and other government agencies.

And placements usually happen only after a school district has proved unable to provide an “appropriate” education in a special education classroom. That can take months, even years. In this calculus, a deteriorating home life, like the one experienced by the Benedicts, receives relatively little weight.

• From FOX 61 in Connecticut: “Governor signs children's mental health bills”

[Connecticut] Gov. Ned Lamont signed several bills into law toward the end of the session including a series of bills prioritizing mental health services for children in Connecticut.

“Obviously we thought we had to do more, especially coming after two years of COVID and we’re going to make a difference in these kids’ lives and if we have to do more, we’ll do more," Lamont said.

[…]Lt. Gov. Susan Bysiewicz said the legislation invests $300 million in expanding treatment, making services more affordable, and helping practitioners take on more clients. The bills also call for the hiring of more social workers and therapists and improvements to emergency services for mental health and substance use-related emergency calls.

• From WSAW-TV (Wisconsin): “Families with children who have special needs face additional barriers to finding child care”

[Mom Samantha Brown said:] “I’m having a harder time now with child care with having a child of mental illness issues and being diabetic, he’s Type 1.”

Though her children attend school full-time, she said she has to be nearby and available at a moment’s notice.

“If there’s (sic) problems at the school, I go to the school. If he’s not having a good day... So, I’m mainly home, you know, but (inadequate) child care has definitely put a damper on working more.”

This single mom works on the weekends at an assisted living facility, in addition to receiving some government benefits. She is going to school part-time during the week to get a degree in substance use disorder counseling and human resources. She said she knows those skills are needed in the community and the hope is she will be able to provide more income for her family too. This allows her to remain flexible with Emercyn’s needs, but it does not alleviate her child care problems.

[…]According to the latest data from February from the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families, 75% of the zip codes in Lincoln County are considered child care deserts, including Brown’s hometown: Merrill. Brown said they do have some resources through the county, which are helpful and they qualify for respite care, but it is up to her to find that respite care.

[…]Several parents told 7 Investigates that they struggle with finding care for their child with special needs. Childcaring, the child care resource and referral agency for the central Wisconsin region also echoed the additional challenge families in those situations face.

Medical Motherhood is a weekly newsletter giving those raising disabled children the news and information they need to navigate complex systems. Get it delivered to your inbox each Sunday morning or give a gift subscription. Subscriptions are free, with optional tiers of support. Thank you to our paid subscribers!

Follow Medical Motherhood on Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or Instagram or, visit the Medical Motherhood merchandise store to get a T-shirt or mug proclaiming your status as a “medical mama” or “medical papa.”

Do you have a question about raising disabled kids that no one seems to be able to answer? Ask me and it may become a future issue.