Today’s Medical Motherhood is a rerun of coverage of a protest one year ago that was asking for parents to be paid as caregivers. Many things have changed in the last year, and much has remained the same: I still think this is a good idea and I have worked alongside a group of passionate parents for many hours every week to try to make it happen. I have also made and lost friends over differences of opinion about what a politically viable strategy is for a policy for Oregon. The parent group I am a part of this week dramatically narrowed our latest request in an attempt to get something through the Oregon legislature this session. It was not an easy decision — and maybe it was the wrong one — but it’s what I and many others felt was necessary.

Tomorrow, April 3, at 3 p.m. is the last chance for Oregon’s Senate Human Services Committee to pass Senate Bill 91 on to the Ways and Means Committee. From there, it will need to be funded and pass the full legislature. After that, our state agency would develop an application to the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare and rules for the program. After alllll of that, there could finally be a permanent program in Oregon that hopefully could grow and expand to include more and more children. It doesn’t feel like a win compared to what should happen — all children with support hours being able to have their parent as their support worker if that makes sense for them — but it’s a long way from the brick wall it felt like one year ago at this protest.

March 2022 — As I drove back from the Family Caregivers Car Caravan at the Capitol in Salem last Thursday, I was struck by the depth of feeling from so many of the people I spoke with there. The love between parents and young children is a world-changing force.

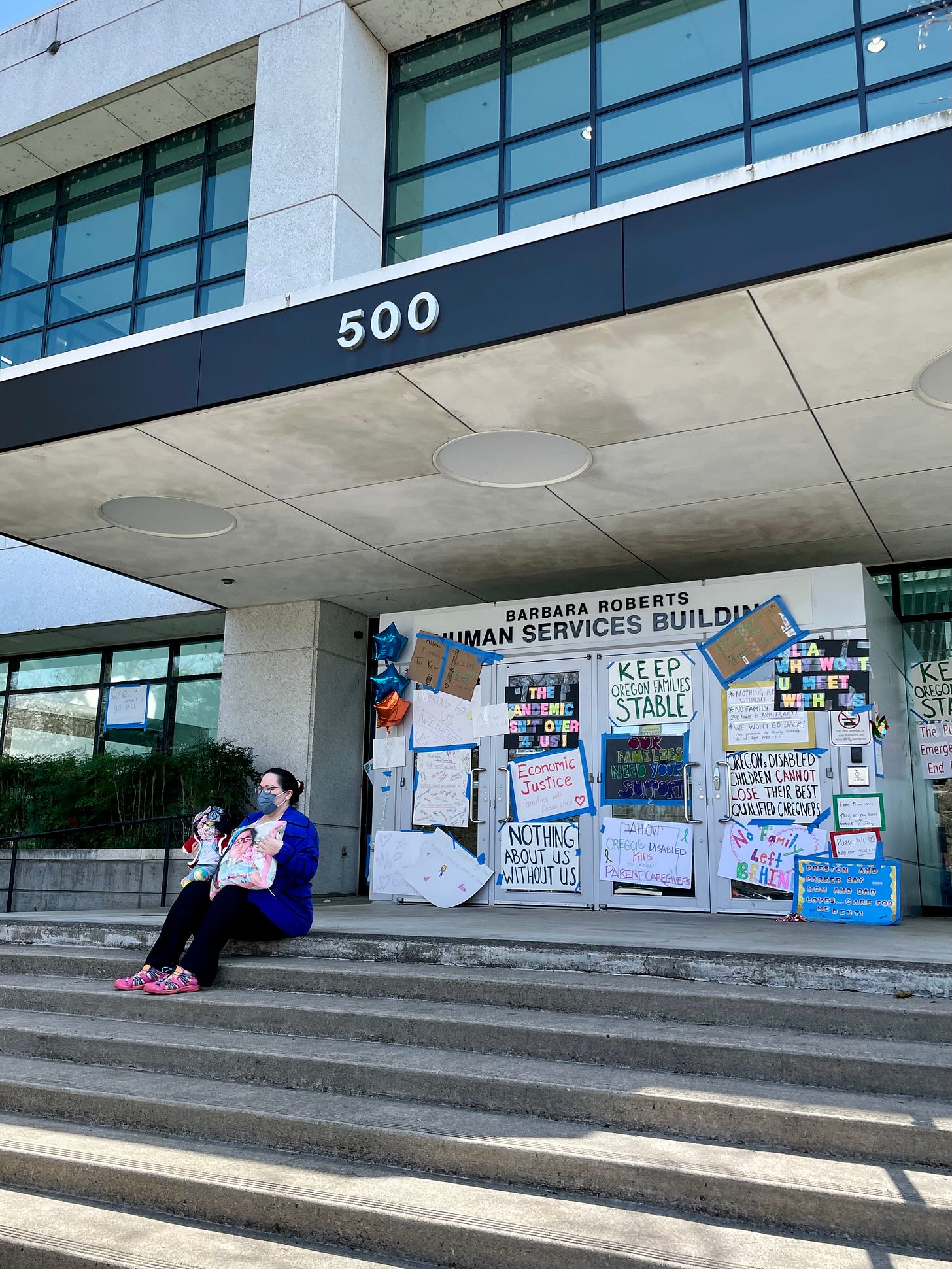

Watch a video of the arrival of the caravan at the Human Services building: https://www.facebook.com/shastakm/videos/501086394888524

In the depths of despair, what do any of us say? “I want my mommy,” right? Even if our relationship with our mother is complicated, we have all known the original safety of a womb.

Children — many too young to fully grasp the economic consequences of these policies — came out with their parents and caregivers and friends to ask Oregon to make paying parent-caregivers permanent. This has been a temporary option in the state due to an exception granted during the COVID-19 public health emergency. The Oregon Office of Developmental Disabilities Services recently announced that it would explore options for a permanent program but was vague on the details.

Supporters — like me — want parents to have a seat at the table when such a permanent program is being devised.

Ideally, the children themselves would be advocating for their own needs, but we parents often find we need to advocate for them until they have enough personal agency.

My 11-year-old twins came down and participated in their own way — the loud noises were a bit of a sensory overwhelm but they stayed in their safe car cocoon and loved the energetic atmosphere.

I have explained the issues to them as best I can — that we love our awesome caregivers but they can’t always be around, so when they can’t it would be nice for mama to get those hours so she can feel like she’s contributing — and to buy the stuff we need to survive and thrive.

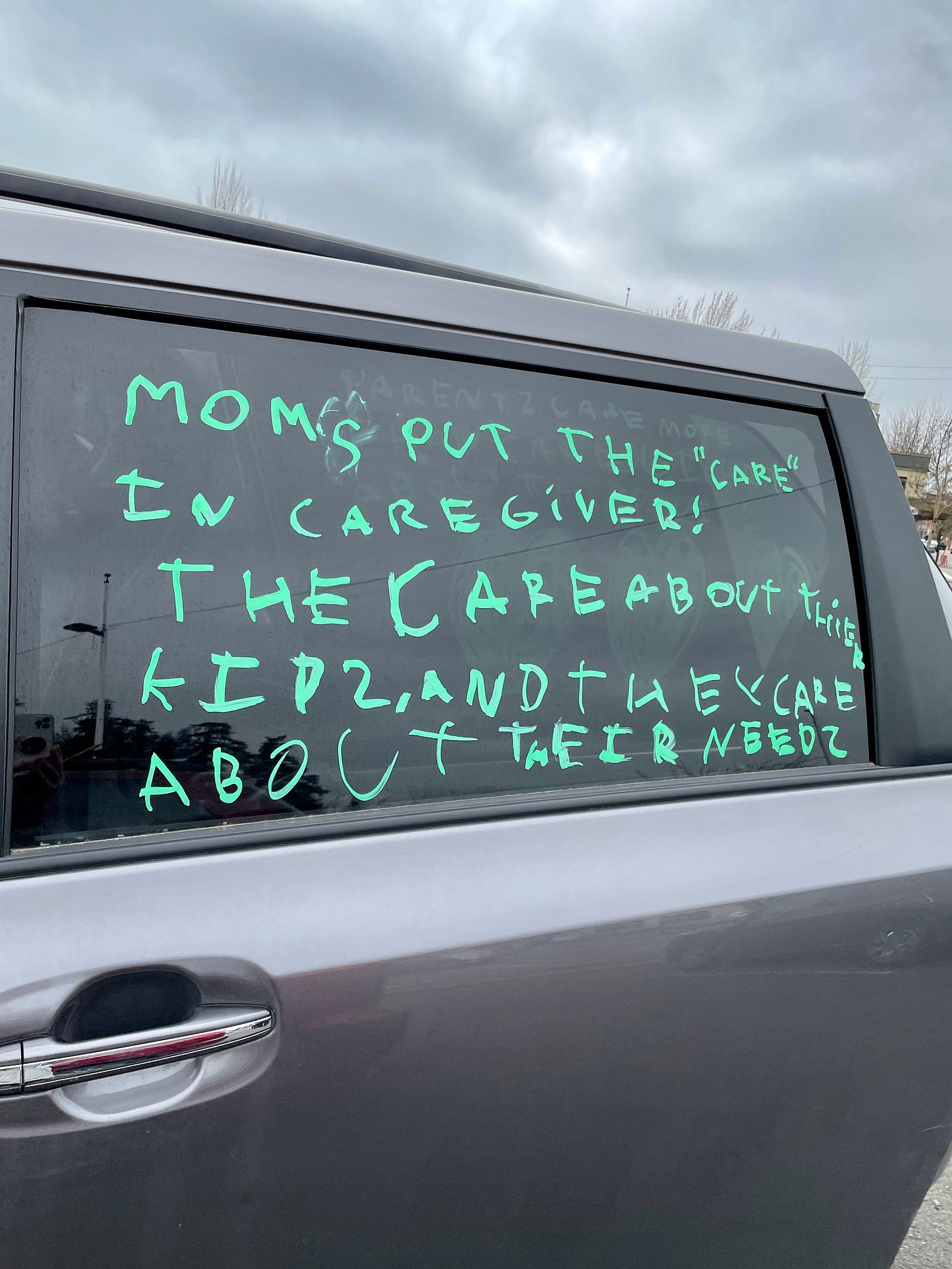

That day, I gave them crayons and poster board and prompted them with a list of slogans they could write if they wanted. But they surprised me.

I thought Mack* would select “A person’s a person, no matter how small,” a quote from his current favorite author, Dr. Seuss. But he chose: “The health emergency never ends for us.” It’s true — COVID-19 was just a variation on a theme for many families with medically complex kids. And, the current labor shortage is particularly acute in the health fields — there are very few caregivers around to employ.

Jasper* skipped my list entirely. He drew a house with a mother and baby and wrote: “Do it for them.” Then, he wrote in bold letters on the side of the car: “Moms put the ‘care’ in caregiver! They care about their kids and they care about their needs.”

At the last minute, Mack surprised me again and said that he wanted to write on the car that other states have this as an option, so I wrote that for him, too.

I tell you all this so you know where my family stands. I wrestle a lot with what political activity I’m “allowed” to do and still call myself a journalist. I used to scoff at people — “citizen journalists” — who would cover protests they so clearly agreed with instead of acting impartially. But the world is ending, the stories I’ve heard have broken my heart, no one else I know of covered this rally, so I can’t bring myself to play a role for the sake of a few imaginary critics. At least on this issue, transparency will have to suffice in the place of objectivity.

As I’ve made clear in previous issues of this newsletter, I definitely have an opinionabout paying parent-caregivers — one acquired through a decade of personal experience, three years of research and dozens of conversations. I welcome a conversation with anyone who disagrees, so please reach out.

So, I bore witness as families of disabled children caravanned around the Capitol, honking and shouting, and ended at the Barbara Roberts Human Services building, home to the Department of Human Services and ODDS. With balloons and signs — which they then taped to the building’s front doors — 24 cars full of people asked their voices to be heard. Families say the temporary allowance for parent-caregivers has improved their children’s health and stability in dramatic ways.

Mick Stevens, a Tigard resident who was profiled in this piece in The Lund Report, came down to protest in Salem with his 12-year-old daughter, Jillian. Stevens has been her full-time caregiver almost all of her life out of necessity.

“I think paying the parents, you’re buying the best caregivers for the money,” he said. Stevens added that Jillian has gained skills and experiences that she wouldn’t have gotten with an inconsistent patchwork of caregivers.

Alicia Bodine drove from Dallas, Ore., with her mom and daughter. Bodine cannot afford to work due to Zoë’s needs, so she has to live with her mom — who is allowed to be a paid caregiver, while Bodine cannot. Bodine said she knows that people will criticize her by saying she chose to have a kid and shouldn’t need government support. “It doesn’t matter, because I know that I’m not a lazy person.”

Mellani Calvin, whom longtime readers will recall I spoke with for this piece on social security, made the trip down from Portland. As head of a nonprofit that helps people apply for social security disability benefits, she says that process is still enormously complicated and has even gotten worse since COVID-19. “Families should not have to work so hard to get what they need,” Calvin said.

Several people told me they couldn’t make it due to last-minute medical emergencies with their children or their ongoing 24-7 care needs. Gabriel Triplett, the rally’s lead organizer, acknowledged that in his kick-off speech.

“There are plenty of people throughout Oregon who can’t make it. Because even though they are getting paid to take care of their kids, they are the only one there. They’ve got nobody else,” Triplett said. “We’ve got plenty of people who couldn’t make it today but we fight for them.”

Triplett’s own children couldn’t come either. Oscar, 9, spoke with me over Zoom using a communication device he operates with his eyes. “One good thing about my parents being home is that I get to spend more time with them. I can’t think of anything bad about it,” he said.

Belen Molina had to call 9-1-1 the night before for her 2-year-old medically fragile daughter, but still managed to make the rally after she got her airway cleared with a suction machine.

“How amazing would it be if I could have the resources for what she needs?” Molina said. “It would mean we could get her more of the expensive things she needs and I would know that she’s always taken care of.” The mother of two disabled children is not currently paid because her daughter’s hours are under the limit of the temporary program.

Sydney McIntosh, who has been a paid caregiver for a decade, said she also supports parents being able to do what she does. “I think COVID has made it really difficult to trust people outside your bubble,” McIntosh said. She added that she had to make a lot of personal sacrifices during the pandemic in order to make sure her clients stayed safe, like social distancing, masking and isolating, even when not required by law. “That’s not something everyone is prepared to do.”

She added that not all families will chose to use the hours to pay a parent, “but it’s important to have the option.”

Calli Ross came from Sherwood on behalf of her 7-year-old son, who has end-stage heart and lung disease. She said under this program her husband no longer has to work two jobs to pay the bills. Ross said it is impossible to fill the 540 hours a month of nursing care her son needs. Except for 18 hours a week, the rest of the 24-7 job falls to her and her husband. Under the temporary program, they have paid off medical debt and bought new medical equipment. “Everything we’re making we’re putting back into my child,” Ross said.

Dr. Satya Chandragiri, a psychiatrist at Salem Health hospital and a school board member for the Salem-Kaizer School District, wandered into the protest and thought it was a great idea. He said he frequently sees patients in his practice who are so completely overwhelmed by the hoops they have to jump through in addition to their child’s extra needs that they don’t end up getting any government support for their kids.

“It’s not just the child that has a disability, it’s the entire family that struggles,” he said. “Even if they have eligibility, getting into the developmental disabilities system is almost impossible, honestly.”

Chandragiri said children can struggle with strangers coming to help them with intimate care needs and have trauma reactions. “I think family are the best caregivers,” he said.

Chandragiri also said he was impressed that so many people could even come to the rally because usually care needs in this population are so unrelenting.

Triplett, the rally organizer, said the temporary policy had given struggling families just enough breathing room to organize for what they needed.

“We need to make this permanent so that we can continue to fight.” And, he added: “We’re out here today because the NICUs across the state are filled with brand new parents who don’t know yet how important this policy will be but will need it nonetheless very soon.”

*Not their real names

A version of this story ran on March 27, 2022.

Medical Motherhood’s news round up

Snippets of news and opinion from outlets around the world. Click the links for the full story.

• From Disability Scoop: “Autism Now Affects 1 In 36 Kids, CDC Says”

Autism rates across the country continue to climb, but for the first time, the demographics of children diagnosed with the developmental disability are starting to shift in a big way, according to new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A report out Thursday in the federal agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report shows that 1 in 36 children, or 2.8%, have autism.

The new estimate is based on information gathered on 8-year-old children in 11 communities in 2020 by the CDC’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring, or ADDM, network.

[…]For the first time ever, the percentages of Black, Hispanic and Asian or Pacific Islander 8-year-olds with autism were higher than white children, which CDC officials said may be a sign that efforts to improve screening, awareness and access to services among traditionally underserved populations are working.

[…]Across the communities studied, autism prevalence ranged from 1 in 43, or 2.3%, of children in Maryland to 1 in 22, or 4.5%, in California. CDC officials said that could be due to differences in how communities are identifying children on the spectrum.

Alycia Halladay, chief science officer at the Autism Science Foundation, said the new data suggests that there is better awareness of autism, particularly among minority communities. But, given that a large percentage of Black children with autism also had intellectual disability and likely had more pronounced symptoms, she said that “there is still a way to go.”[…]

• From WBUR (Massachusetts): “In Oregon, some students with disabilities are fighting 'an uphill battle' to go to school”

Democratic state senator Sara Gelser Blouin of Oregon says parents are concerned that some children with disabilities are not getting equal access to school.

Schools implement abbreviated school day programs, she says, when they claim they don’t have adequate staffing to meet student needs. Now she has a bill making its way through the state legislative session that aims to address the issue.

“Some students don't even get to start kindergarten with a full day of school,” she says. “They are welcomed to elementary school by being put on an abbreviated school day… that could be 25 minutes a week of online instruction and that's it.”

Elizabeth Miller, an education reporter at Oregon Public Broadcasting, says parents have been complaining about the practice for years.

“I reported on a family who moved to Idaho instead because their student wasn't receiving the services they felt they needed,” she says. “It's a tough situation.” [Read the full transcript of the interview at the link.]

• From Philstar.com in the Philippines: “Landmark law for children with disabilities still unimplemented a year since passage”

[…] Advocates of inclusive education and persons with disabilities lauded the passage in 2022 of a landmark law [in the Philippines] that would pave the way for improved programs and services for learners with disabilities.

Republic Act 11650, or the Inclusive Education Act, was signed into law in March 2022. It mandated all cities or municipalities to establish an Inclusive Learning Resource Center (ILRC) – a physical or virtual one-stop-shop providing teaching and learning support to students with disabilities while providing free therapy services.

While the passage of the law was hailed as a beacon of hope for children with disabilities, a year later, the government has yet to release its implementing rules and regulations (IRR), which would have moved the needle closer to ensuring students with disabilities had access to quality education and health services.

[…] "There are still a lot of schools that turn away students for the simple reason that they will say: ‘We are not trained. We don’t want to short-change the child,’" [Special education teacher Cristina] Aligada-Halal said in a phone interview with Philstar.com.

"What happens is that it now becomes mostly the parent’s accountability. It’s like, you enrolled your child there knowing that it is not an inclusive institution. It becomes mostly their choice and burden to bear," she said.

[…]E-Net Philippines, a civil society network of education groups, called on the government on March 22 to lay down clear guidelines on how to implement the law, which is meant to address the education and health needs of around 5 million Filipino children with disabilities.

[…]Aligada-Halal, who is also a member of the ADHD Society of the Philippines, said that some parents of children with ADHD she has spoken to are now "skeptical" a year after the disability sector celebrated the passage of the law.

"The conversation on disability rights has changed. Last year, when it was newly signed into law, everyone was so hopeful. But then towards the latter part of the year, (we saw that) nothing changed," she said.

"Schools don’t feel compelled to act on it because they are also waiting for instructions," she added.[…]

Medical Motherhood brings you quality news and information each Sunday for raising disabled and neurodivergent children. Get it delivered to your inbox each week or give a gift subscription. Subscriptions are free, with optional tiers of support. Thank you to our paid subscribers!

Follow Medical Motherhood on Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram or Pinterest. The podcast is also available in your feeds on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. Visit the Medical Motherhood merchandise store.

Do you have a story to share or an injustice that needs investigation? Tell me about it and it may become a future issue.