Lack of sleep is definitely my Kryptonite! What’s yours?

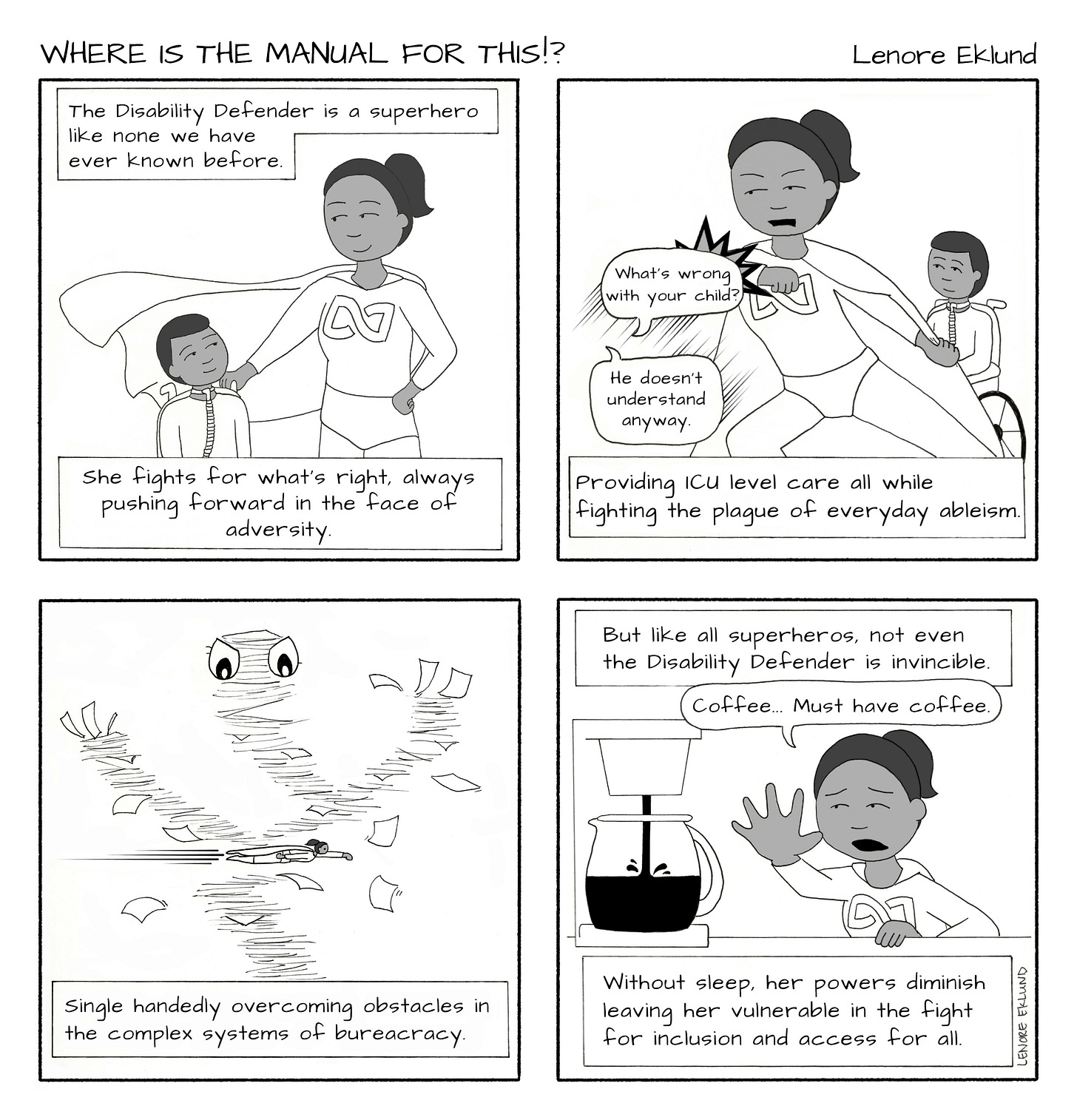

The second Sunday of every month Medical Motherhood publishes Where Is the Manual for This?!, an editorial cartoon by Lenore Eklund.

Medical Motherhood’s news round up

Snippets of news and opinion from outlets around the world. Click the links for the full story.

• From the Miami Herald: “‘Just another baby for them.’ Parents, feds fight for kids stuck in Florida nursing homes” (If you decide to click through, be aware that the article contains numerous graphic descriptions of abuse and poor living conditions for disabled children.)

Court records in a federal lawsuit set for trial on Monday before U.S. District Judge Donald M. Middlebrooks in West Palm Beach […assert…] that Florida’s reliance on […] institutions for the care of fragile children is a violation of their civil rights and an affront to federal laws that require the housing and treatment of disabled people in home-like settings whenever possible.

[…]

Mary L. Ehlenbach, the medical director of the Pediatric Complex Care Program at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, wrote in a report that parents often are held to a higher standard than the institutions that are being paid hundreds of thousands per year. Some parents, for example, said nursing home administrators told them their children couldn’t go home until the family had a large private bedroom for the disabled child. At the nursing home, though, the children sometimes live three or four to a room.

“Parents don’t want their children exported to institutions 300 or 400 miles away to be warehoused,” said Dr. Jeffrey Goldhagen, the division chief of community and societal pediatrics at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville.

Brittany Hayes, the mother of a 5-year-old boy who has spent his entire life in nursing homes, told the Herald: “Most of the time he’s in a crib. Every time I Facetime him, he’s laying down in the crib.” “If they’d just give me my child, I would make sure he meets his goals,” Hayes said. “He’s just another baby to them.” Responding to “multiple complaints” about the institutionalization of disabled children, the Justice Department’s civil rights division sued Florida health administrators a decade ago to put an end to such practices, saying they violate federal laws forbidding the institutionalization of disabled people, especially children.

[…]The state insists that the federal government should mind its own business and allow Florida health regulators to provide care to disabled children as they see fit. The lawsuit, state lawyers say, cuts to the very “heart of its sovereignty: the weighing of competing healthcare policies.”

[…]Parents told experts that nursing homes made it nearly impossible for families to bring their children home, describing discharge planning as an endless series of moving goal posts. One parent expressed immense frustration at efforts to bring their child home from a nursing facility. “No matter who I scream at, nothing gets done,” the parent told Ehlenbach.

Wrote Ehlenbach in her report: “Several families described feeling desperate to be reunited with their children. One family member poignantly shared, ‘Pretty much short of robbing a bank, we’ll do what we can to bring him home’.”

• From The Washington Post: “‘Medical moms’ share their kids’ illnesses with millions. At what cost?”

When Bella was born in 2013, she didn’t leave the hospital for the first two years of her life because of a combination of a rare form of dwarfism, bowel disease and autoimmune disease. Kyla Thomson, Bella’s mom, started sharing online as a way to update her family members.

As Bella grew and changed, so did the internet. Kyla moved her updates from blogs to Facebook to Instagram, eventually landing on TikTok, where she has amassed 5.7 million followers. Fans watch Bella and Kyla dance and joke and follow Bella’s hospital stays, ambulance rides and nightly intravenous medication rituals.

Thomson’s account is one of the biggest in the world of #medicalmoms, a corner of TikTok where mothers of disabled and chronically ill children share their parenthood journeys. Among the posted videos: a child with cystic fibrosis struggling to breathe, a premature baby getting their tracheotomy changed, and a mother dancing to a trending song while words pop up explaining her child’s disability.

The parents behind these accounts say they’re sharing the content to raise awareness about the realities of disability, fight social stigma and foster a community for others in their situation. But as scrutiny of influencer parents sharpens, some creators are walking back old decisions to share their kids’ faces and deleting old videos. Advocates are introducing legislation to protect influencer kids and pushing against the monetization of child-focused content. And critics say issues of child privacy, consent and autonomy are especially pronounced when publicizing medical conditions.

[…] Annalise Caron, a clinical psychologist who runs an initiative dedicated to parenting, understands the instinct parents have to seek community.

“It can be a very lonely experience to be a parent of a chronically ill child,” Caron said. “Parents find support online.”

But two questions arise, Caron said, that are worth asking before sharing photos or videos of your child. First: what is the goal in sharing this? And second: how does my child feel now and how will they feel in the future?

“We could ask someone when they’re six or eight, ‘do you mind if I talk about your personal medical information?’ They might say, sure,” Caron said. “But maybe when they’re 16 and they find out their parents have a huge following off them, they may not be as comfortable with that.” Even if sharing a child’s experience helps build community, Caron said, the child’s privacy and personal feelings should always be considered first.

• From the Chicago Tribune (opinion): “Lauren Rivera: Are principals steering disabled children away from their schools?”

Many parents want to find schools where their children will thrive. But for parents of children with disabilities, the stakes of finding a good school cannot be higher.

Parents’ concerns range from whether a school will have the right services and supports to help their child advance academically, to whether the school can keep their child physically safe. In some cases, having that information, which is not publicly accessible and often obtained through directly contacting school officials or participating in school tours, can be lifesaving. But discrimination can prevent families from gaining such crucial knowledge.

I faced this situation while researching a possible move from Chicago to New York. A major part of the decision was finding appropriate schooling options for our able-bodied son and physically disabled daughter. Scheduling tours of schools in both cities for my son was easy but proved tricky for my daughter. When I mentioned her disabilities in email or phone requests, far fewer schools replied to me. When they did, they often declined a tour, telling me that they did not give tours as policy (even when I knew other parents that had successfully toured) or would provide a tour only after I purchased a home in their catchment zone.

One administrator even told me over the phone, “You can come tour our program if you look through the eyes of your (able-bodied) son. But not if you look through the eyes of your (disabled) daughter.”

[…]We conducted an audit study of more than 20,000 K-12 public schools in four states. We emailed school principals, telling them that we were moving to the area and researching schools for our child. We asked if we could set up a school tour. Half of the emails indicated that the child had a disability, signaled with an individualized education plan (IEP); the other half did not. Because disability intersects with other identities, we also varied the perceived gender of the child and the race of the parent.

[…] We found that principals were indeed significantly less likely to grant tour requests when they believed the child was disabled versus nondisabled, an effect that was even larger when they believed the parent was Black. Most principals did not outright say no. They simply chose not to respond. We conducted a follow-up experiment of 578 principals to understand factors motivating this behavior. It turns out principals viewed disabled students as imposing a greater financial and temporal burden on their schools. Potentially to preserve resources, they engaged in a subtle form of exclusion: strategic avoidance.

[…] What can policymakers do to create a more inclusive landscape that discourages local school officials from isolating, removing, or ignoring disabled students or their families? Fully funding special education at 40% is an important start.

Medical Motherhood brings you quality news and information each Sunday for raising disabled and neurodivergent children. Get it delivered to your inbox each week or give a gift subscription. Subscriptions are free, with optional tiers of support. Thank you to our paid subscribers!

Follow Medical Motherhood on Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram or Pinterest. The podcast is also available in your feeds on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. Visit the Medical Motherhood merchandise store.