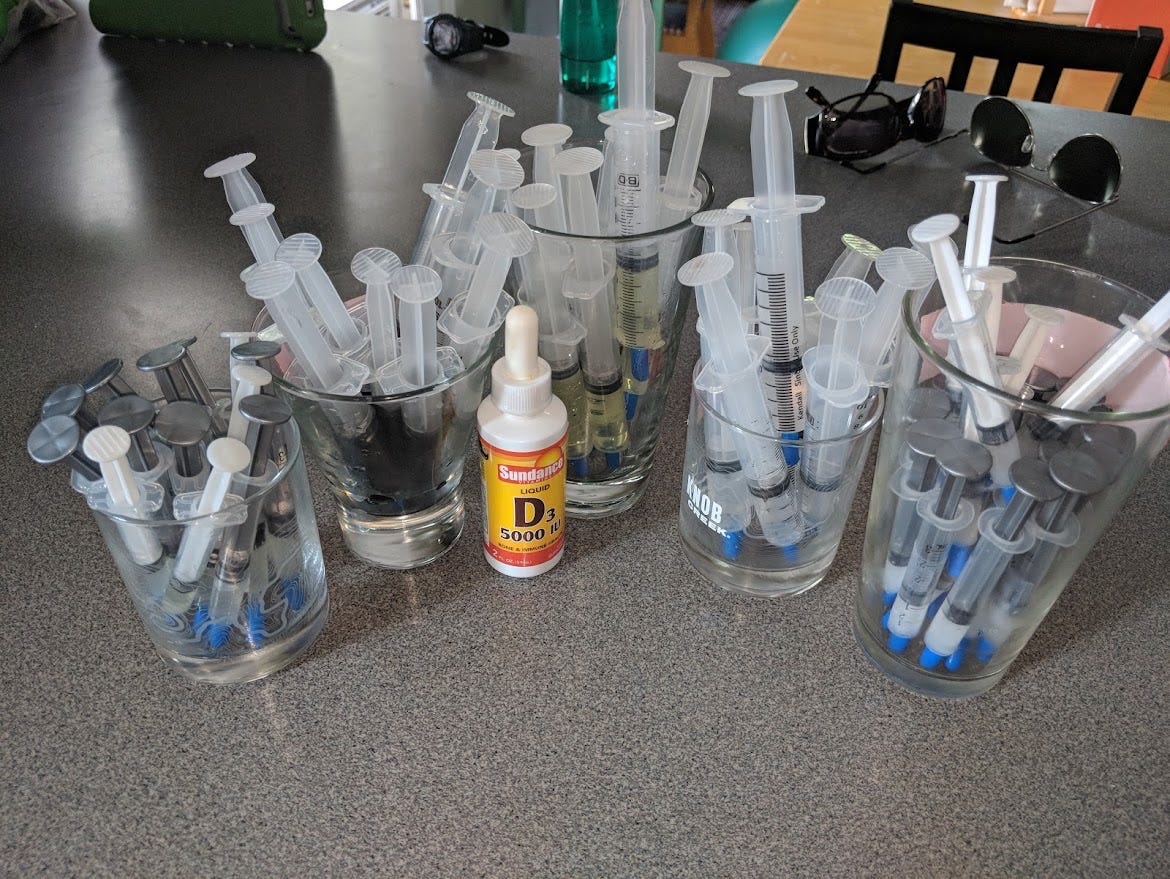

Each week, we showcase a picture of real life from the Medical Motherhood community. If you’d like to participate, simply reply to this email. The intent is to show YOUR experience as a medical parent, not your child. What do you want people to know about the #medicalmom life?

Medical Motherhood’s news round up

Snippets of news and opinion from outlets around the world. Click the links for the full story.

• From The 74: “They Stood Up to NYC Schools for Their Disabled Child. Then Child Protective Services Arrived”

When their 7-year-old son, Tristan, who is autistic and nonverbal, arrived home from school with bruises and a lump on his head, Bronx parents Luis and Michelle Diaz began to worry.

They asked the school to look into the 2021 incident and requested a new paraeducator for their child. The classroom aide hadn’t mentioned the injury, despite messaging them throughout the day, the parents said, erasing their trust in her.

But the family’s search for answers and solutions brought them head-on into a problem they hadn’t anticipated: The school pointed the finger back at the Diaz parents, alleging neglect and inadequate supervision of their child. Soon, a caseworker with the Administration for Children’s Sevices, known as ACS, the New York City agency responsible for investigating suspected child abuse, showed up at their door.

“We were just trying to advocate for our son and find out what happened like any parent would,” Michelle Diaz said. “This is where the retaliation started.”

The school’s response reveals a startling pattern: Across the nation’s largest district, parents of students with disabilities who speak up on behalf of their children say they are being charged with allegations of child abuse or neglect — a tactic advocates say schools use to intimidate parents and coerce them into dropping their concerns.

Though it’s not clear how many reports may be retaliatory, New York City educators have made more than 3,500 calls alleging suspected abuse or neglect of children with disabilities over the past two school years, according to data obtained by The 74 through public records requests. Each one triggers an intrusive process that, at its most dire, can lead to the removal of a child from parents’ custody. Yet caseworkers found evidence of parental wrongdoing in only 16% of cases, and fewer still go on to withstand judges’ scrutiny.

In more than a dozen interviews, parents, advocates and researchers recounted what they described as a common practice of threats leveraged against families of some of the most vulnerable students in the city’s school system.

“Those are intimidation tactics that they do to parents,” said Rima Izquierdo, a Bronx parent leader who supports families of special needs children across the borough.

“This is a trend. … All the stories sound the same.”

Neither the Department of Education nor ACS responded to parents’ claims of retaliation when asked in an email. DOE spokesperson Nicole Brownstein expressed her agency’s commitment to “the safety and wellbeing of our students.”

[…] In 2022, the federal Office of Civil Rights received 1,708 retaliation complaints from families of students with disabilities. Numerous parent blogs describe anecdotal cases where schools have used child protective services reports or truancy charges to punish families advocating for their special education children. And the American Bar Association published a 2019 brief on the legal rights of parents of special education students who find themselves facing these allegations.

Previous reporting has revealed cases where schools weaponize the threat of calling child protective services against parents who aggravate educators or administrators. But families of special education students say they are at particular risk for the unlawful treatment.

It’s “a very common occurrence,” said Anna Arons, a New York University law professor, that when families have “substantial back-and-forth with the school about the appropriate services for their child” it can result in educators calling the state child abuse hotline.

School staff are one of several professions legally obligated to report suspected child abuse and neglect. But in New York City and nationwide, educators make a higher share of unsubstantiated calls than any other mandatory reporter category — meaning families often become needlessly ensnared in a process they describe as invasive and traumatic.

[…]An ACS spokesperson said in an email that the agency is working with educators and school leadership to reduce the number of families coming into unnecessary contact with the child welfare system, training educators to instead connect struggling families with resources like food or rent support. The agency runs several community centers across the city that offer free resources to families, such as clothing, food and diapers.

“We will continue to work with stakeholders, like NYC Public Schools, to help reduce unnecessary reports so that we can better focus our child protection resources on those who really need it,” the spokesperson said. […]

• From KFF Health News via Clinical Advisor: “As Medicaid Purge Begins, ‘Staggering Numbers’ of Americans Lose Coverage in 2023”

More than 600,000 Americans have lost Medicaid coverage since pandemic protections ended on April 1, 2023. A KFF Health News analysis of state data shows the vast majority were removed from state rolls for not completing paperwork.

Under normal circumstances, states review their Medicaid enrollment lists regularly to ensure every recipient qualifies for coverage. But because of a nationwide pause in those reviews during the pandemic, the health insurance program for low-income and disabled Americans kept people covered even if they no longer qualified.

Now, in what’s known as the Medicaid unwinding, states are combing through rolls and deciding who stays and who goes. People who are no longer eligible or don’t complete paperwork in time will be dropped.

[…]Tens of thousands of children are losing coverage, as researchers have warned, even though some may still qualify for Medicaid or CHIP. In its first month of reviews, South Dakota ended coverage for 10% of all Medicaid and CHIP enrollees in the state. More than half of them were children. In Arkansas, about 40% were children.

Many parents don’t know that limits on household income are significantly higher for children than adults. Parents should fill out renewal forms even if they don’t qualify themselves, said Joan Alker, executive director of the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families.

New Hampshire has moved most families with children to the end of the review process. Lipman said his biggest worry is that a child will end up uninsured. Florida also planned to push children with serious health conditions and other vulnerable groups to the end of the review line. But according to Miriam Harmatz, advocacy director and founder of the Florida Health Justice Project, state officials sent cancellation letters to several clients with disabled children who probably still qualify. She’s helping those families appeal. […]

• From The Guardian: “Australia’s kinship carers desperate for support as numbers of children in out-of-home care grow”

[…] Kinship and foster carers are facing increasing financial pressures amid the cost of living crisis and only marginal rises in government allowances. Advocates say the exit rates mean more children are placed in institutional care homes, considered a last resort.

Since 2019, Jane has cared full-time for her two grandchildren, aged eight and four, after she spent two decades as a foster carer. Her grandchildren are the 64th and 65th children she has opened her home to.

“I wanted to give children a better chance than the one I’d had. I wanted to give them a safe haven,” she says.

Jane says despite begging for monetary support from the Victorian government, she was only provided with one single bed, despite caring for two children. She says support to nurture the children’s First Nations culture was limited to a pencil case printed with Indigenous artwork.

Compared to her time as a foster carer, Jane says being a kinship carer is akin to being “the poor cousins” of the protection system.

[…] The CEO of Victoria’s foster care association, Samantha Hauge, says current funding is inadequate and put carers in an impossible situation.

“Either they pay for services out of their own pocket (with the hope that they might be reimbursed at some stage in the future) or let the children go without,” she says.

The association praised the state’s budget providing a one-off $650 supplementary payment for each child for all foster and kinship carer households, but says there is no funding to increase the care allowance.

Kinship Carers Victoria says the budget initiatives would not allow carers to “lift themselves out of poverty.” […]

Medical Motherhood brings you quality news and information each Sunday for raising disabled and neurodivergent children. Get it delivered to your inbox each week or give a gift subscription. Subscriptions are free, with optional tiers of support. Thank you to our paid subscribers!

Follow Medical Motherhood on Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram or Pinterest. The podcast is also available in your feeds on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. Visit the Medical Motherhood merchandise store.