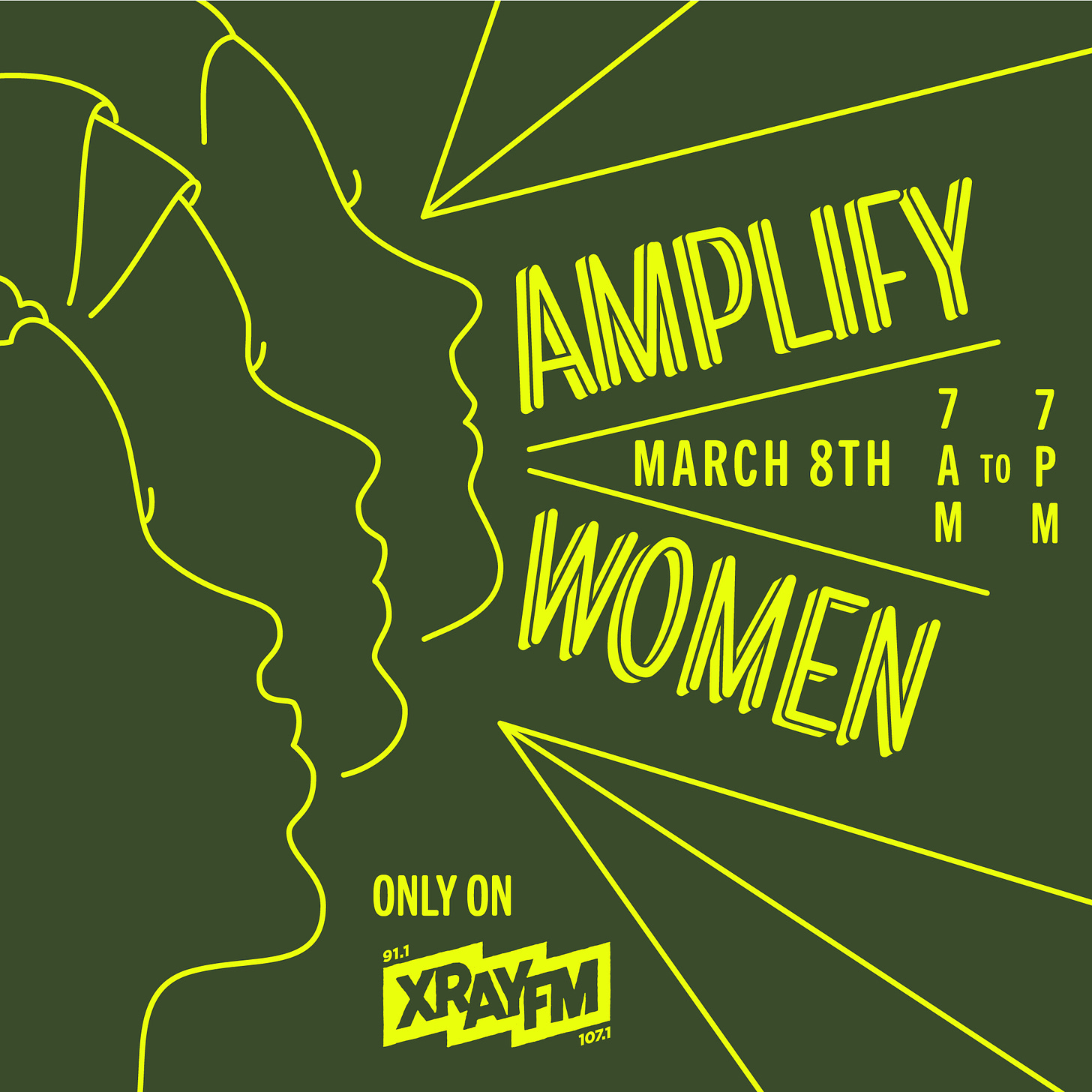

Each year on International Women’s Day, a Portland, Ore., radio station “holds the mic up to those systematically excluded from radio, 365 days a year.” From 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., all other programming is suspended to put marginalized people’s struggles into sharper focus. As part of this Amplify Women event, XRAY FM aired a conversation I recorded with three women at 11 a.m. last Wednesday, March 8. (See it on their site at Medical Motherhood: Full-Time Paid Caregiving for Parents of Disabled Children.)

In the podcast version of this week’s Medical Motherhood, you can listen to the full hour between myself and Tina Stracener, the mother of a medically fragile 17-year-old; Lisa Ledson, a registered nurse and mom to an autistic 10-year-old with cerebral palsy; and Romi Ross, a certified behavior specialist and mother of a 9-year-old with high behavior needs. All three have been working to try to pass paid parent caregiver legislation this session in the Oregon legislature. Senate Bill 91 and Senate Bill 646 are — as of this writing — waiting for a work session to be scheduled in the Senate Human Services Committee. If that doesn’t happen by March 17, the measures will die in committee without a vote.

Full disclosure: I have lobbied on behalf of these bills and my son would benefit from either of them if passed. I am also friends with Tina, Lisa and Romi — three amazing women whose stories and perspectives I’m delighted to be able share with you.

Because of the length of the podcast, there are no news briefs this week but they will be back next week. You can find a full (computer-generated) transcript here for those who need or would like to have that.

As part of our conversation, I asked all three why they thought they should be able to be paid to be their child’s caregiver and here’s what they said:

Tina Stracener

The main reason is my daughter wants it. It would be her choice to have me, as her parent, take care of her. I'm her playmate. I'm her mother at her home. She's the heart of the home and I'm the best qualified to care for her. I have 17 years of experience … trying to navigate her very complex seizure disorder. I know the nuances: What is a seizure, versus what is just a silly laugh that some people might not notice. They might see her little laughter and think it's just a laugh. And actually, I know that that's gonna snowball into a seizure that could be life-threatening. It's just the years of experience that have taught me how to navigate that.

Over the last three years of the pandemic, she has not been hospitalized not once. I credit a lot of that to — not only the care that I give — but the fact that there aren't so many people coming in and out of our home, you know, exposing her to various illnesses. This is starkly contrasted to her being hospitalized, sometimes monthly, for the first 14 years or 15 years of her life. So that’s the main reason I wanted it. It's my choice to take to care for her. I love caring for her and I want to be that for her. And I know how to play with her. And so, it just helps make the house feel more like a home.

Lisa Ledson

My personal opinion is that each child is very unique and individual. [I’ve been] an emergency department nurse for 16 years exclusively in the Portland metro area. I've seen over the years how care has changed. But the one thing I believe that has stayed true is the love of the family, especially family caregivers, and how specific and personal they get when it comes to care — and how not personal and specific I am as your ER nurse or the bedside nurse in whatever unit your kid ends up visiting in hospital.

I have twin girls, one of them is significantly disabled, she uses a wheelchair, she has a g-tube to eat with. And she has lots of seizure disorders — about five different styles of seizures. So, technically, she has epilepsy. And as a parent — that parent hat and that nurse hat get merged. And all I can think about is how tough that decision-making processes is and how specific it has to be when you're a parent of a medically fragile [child] or a child with behavioral needs like mine, who has autism as well. When I'm trying to make those decisions, I don't know how to teach those decision-making processes to others. I don't. I don't know how to do that, quite frankly, it's very challenging. So when I've had to do it — I'm training a new personal support worker for us in the home — it's lended itself to be extremely challenging. There are — just like you said, Tina, about June and her seizures — there are certain seizure styles that my daughter has that I only know them. I could try to describe them, like I do to the school staff, and it just doesn't work. They get missed. And that's very scary for me as a parent. So that would be my primary reason as to why there's just those things we know about our kids that you can't teach.

I think I'm gonna leave it at that. I have about 500 other reasons.

Romi Ross

The support for kids with high behavior support needs really does differ. There are some overlaps, of course, there is ADL [Activities of Daily Living] supports, there's medication supports. But for behavior kids, we're often predominantly talking about behavior management, which can be anything from really carefully controlling the environment and setting — every nuance, every detail — up for success, to responding to problems that arise responding to behavior, like physical aggression, or self injury, or other dangerous behaviors like that. Responding to these types of behaviors can mean using really elaborate protocols designed by the child's therapist and support team, and could include physical interventions. Often, they do include physical interventions. And then, on the extreme end of that, that can include restraints.

So when we're talking about the child's welfare, of course we want the people who are going to be using these types of interventions, we want them to be the people who have the most training, who can show up with the most love and the most connection. And, really importantly, the person with whom the child feels the most safe. Because these are potentially traumatizing situations for everybody involved. There needs to be that safe connection there. You know, it's not easy: Staying calm and nurturing when somebody is trying to hurt you. We humans have instincts, and they kick in when we're being attacked.

I work with a lot of DSPs (Direct Support Professionals) professionally, in care homes, and [they are] the most loving people and the most hardworking people. But there is an instinct that kicks in and it is hard to overcome that. It takes a long time to overcome that and to be safe.

I think that there's a connection there with parents that bypasses that — that allows you to do that. In addition to all the training that we get from, you know, the neurologists, the psychologists, the OT, the speech, the behavior therapist, all of that.

*NOTE: Typically on the Second Sunday of the month, Medical Motherhood runs our editorial cartoon Where’s Is the Manual for This?! but because of the timing of International Women’s Day, the cartoon will run a different week.

Medical Motherhood brings you quality news and information each Sunday for raising disabled and neurodivergent children. Get it delivered to your inbox each week or give a gift subscription. Subscriptions are free, with optional tiers of support. Thank you to our paid subscribers!

Follow Medical Motherhood on Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Instagram or Pinterest. The podcast is also available in your feeds on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. Visit the Medical Motherhood merchandise store.

Do you have a story to share or an injustice that needs investigation? Tell me about it and it may become a future issue.

Three moms on why they should be able to be paid caregivers for their children